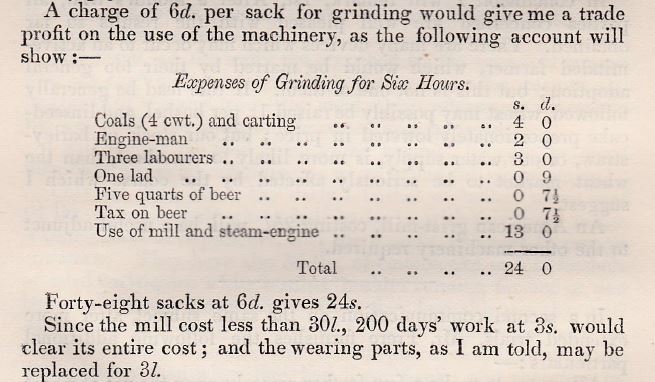

In 1864 a Cambridge gentleman farmer and agricultural scientist, Philip Howard Frere by name, wrote up his experiments in feeding various combinations of fodder. He shared with the readers of the Journal of the Bath and West of England Society that by spending £25 on an “American Grist Mill” (American in name only as it was one of thousands made by Riches and Watts in Norfolk) he could mill for other farmers, make a profit and in three years recoup the cost of the machine as well.

Economics and the Victorian Farmer might seem a dull enough subject, but seven little lines can tell an awful lot about life and its quality among the agricultural labouring community.

Look more closely at his list of costs for what amounted to best part of another day’s work after the end of the working day. A bit of background: The amounts listed are in shillings (s) and pence (d). And you need not worry much that there were in fact 12 pennies in a shilling and 20 shillings in a pound. Those English eh? They could actually add and subtract this stuff in their heads in those long ago days.

I would have liked to ask Frere what he meant by the last cost, listed as Use of Mill and Steam-engine because he seems to have owned it and calls it “my locomotive steam engine”, but as he is more than a little dead by now, we’ll let that pass. What is more important are the first six lines.

Here’s what I saw in the figures:-

Energy costs were huge in relation to labour costs.

Skilled labour was well rewarded in comparison with unskilled, with the engine man getting twice as much as the grunt workers.

Young men were introduced into the labour force at a lowly wage and were doubtless made well aware of their station in life by the men.

And then we come to the next item – five quarts of beer. It was part of Frere’s cost structure of doing business. It served both to hydrate and at the same time placate the workers engaged as they were in meaningless, repetitive and strenuous work.

Last of all, you see that the government took its cut out of the beer — and it was a hefty chunk too. Frere had to pay tax equivalent to the cost of the liquor itself. The British tax structure has relied on the fact that the British like their drink.

As I said, there is much to be gained from what otherwise might appear dry as dust statistics. I only hope that you can see these four men from the same village or a nearby one, labouring on into the summer evening. The older man who works the steam engine has the role as foreman and this is marked out for all to see by the wearing of the bowler or Derby hat. Can you see the boy who treads carefully among the seniors and is the butt of every practical joke going? “Fetch me a left-handed screwdriver boy…” As the evening goes on and the drink takes effect they strike up songs – tales of ploughmen, lusty millers, bold grenadiers, maidens and lilies. Perhaps one of them does a little step dance as they work. Eventually as the last sack is emptied, they dutifully pack up and tidy the barn, then depart, still singing quietly so as not to wake the village, with only the engine man remaining to dampen the fire and rake out the coals.

All from seven lines in an account book.