Everybody needs a hero. Here is one of mine. Why my interest in this man? He is inexorably bound up in a number of book projects I am working on. The next has the working title of An Infinite Deal of Nothing. It is the tale of the two most audacious worldwide frauds of the 19th century that were discovered within months of each other. The Great Diamond Hoax and the Emma Mining fraud involved my hero, but he was an innocent bystander in the wake of another whose fingerprints can now be proven to have been linked to both these confidence tricks.

August 30 marks the death in 1899 of one of the richest men in England of whom you have never heard. Buried in a quiet Sussex churchyard by the sea lie the earthly remains of Albert, Baron Grant.

Where to start?

- He was once so eye-wateringly rich, he bought Leicester Square when it was under threat of redevelopment, just to give it to the nation. He threw in a Landseer portrait of Walter Scott for good measure.

- He was the son of an immigrant from Poland who escaped the pogroms at the aftermath of Napoleon’s Russian campaign.

- Albert Grant was twice Member of Parliament. He was kicked out of his seat after his second election — for promising the voters a street party with penny buns if he won.

- For decade or more, his one-man merchant bank financed the majority of the world’s infrastructure projects seeking funding in the City of London

- He fell from being the most famous banker to the most infamous.

- He owned a national evening newspaper and a slew of magazines. He was perhaps the first person to consider that all-day news was a concept worth exploring.

- He spent the last 20 years of his life endlessly fighting to regain the prominence he had in his thirties though he never did — sinking further into obscurity. Nevertheless, when he died, hundreds (and that is not blind hyperbole, I mean hundreds), of newspapers around the world (and I do mean around the world) carried obituaries recounting his colourful career.

- He built three grand houses — one of which was a 90 room palazzo in the centre of

Kensington. Built and completed at huge expense, he never got to live in it before the creditors took it away. You can still walk up its marble staircase — if you ever visit Madame Tussaud’s in London

Kensington. Built and completed at huge expense, he never got to live in it before the creditors took it away. You can still walk up its marble staircase — if you ever visit Madame Tussaud’s in London  The king of Italy made him a baron for his financing of this magnificent shopping arcade next to the Duomo in Milan.

The king of Italy made him a baron for his financing of this magnificent shopping arcade next to the Duomo in Milan.

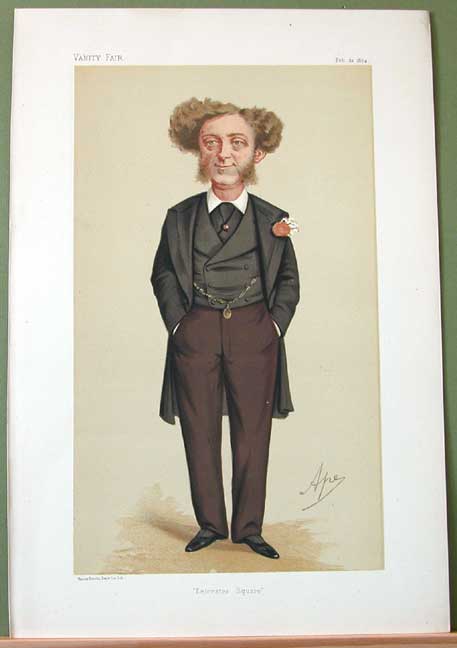

You knew you’d made it when you got your cartoon in Vanity Fair - He and his wife, the daughter of a slave-owning Dominica sugar planter from Northern Ireland, had 12 children. Of the boys one became a decorated professional soldier hero, wounded leading his regiment at the Battle of The Somme, while the girls lived out their lives in genteel spinsterhood.

- Albert changed his religion. Born into a religious reform Jewish family, he had himself Christened before his marriage and was seemingly a devoted member of the Church of England for the rest of his life.

- He changed his name. He was born Abraham Gottheimer.

- In London as a child he worked for the family retailer that sold imported French musical boxes clock parts automata and other knick knacks.

- In his first office job worked alongside a stutteringly shy West Country boy who would become the Victorian era’s most famous actor, Sir Henry Irving.

- In business life he had one vice. He paid off journalists to write up his new companies. He was by no means alone in this and all the scribblers expected a little something, but it was the start of his undoing.

- He might now be seen as much a victim in some of the dubious ventures he floated as the hapless investors

- Even after his death he was vilified. The Dictionary of National Biography set the tone which has continued to this day that the man was a crook and shyster; he was neither.

I wrote the biography some years ago. Here’s a brief excerpt from toward the end of the book:- “The burial did not go well. As his oak coffin was carried outside to the open grave beside the far wall of the churchyard, some distance away from shelter, the heavens opened and 20 or so of the 50 mourners somewhat disrespectfully chose to stay inside the church. The local paper put it this way: ‘The rites at the graveside were very brief, being performed in a storm of rain’.” Now you see why we perhaps need to put a metaphoric pebble on the grave of this larger than life character. The real grave is not looking so good…

Now you see why we perhaps need to put a metaphoric pebble on the grave of this larger than life character. The real grave is not looking so good…