My last folksy yarn about the mad as hell Italians who wanted to scatter bits of Mr and Mrs Napoleon III across Paris that winter evening in 1858 left us in a bad place. We learnt that two of the three condemned men sentenced to die were executed by guillotine, shoeless and in long nightshirts – seemingly de rigueur dress, or undress, stipulated in law for the perpetrators of the crime of parricide, or father murder, after they dared to blow up the father of the nation.

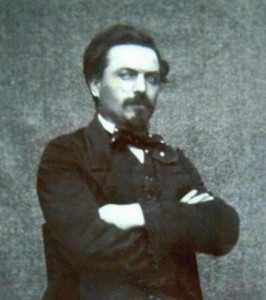

But a third man was not for the chop. To paraphrase Samuel Beckett, “one of the thieves was saved”. Minutes before the execution, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Carlo di Rudio was his name (though the di and de were often interchanged and eventually Carlo would become Charles). di Rudio would almost have wished for death as he soon discovered how the French treated their political prisoners.

Let’s go back a bit: Count Carlo di Rudio was born into minor aristocracy in Belluno, 60 miles north of Venice, in 1832. That put him in the Austrian controlled part of what is now Italy. At first it was a side in which he seemed comfortable. Destined for the military, from age 13 he wore the grey and red uniform of a cadet at the Austrian-sponsored Milan Military Academy of San Luca.

In March 1848, the sixteen-year old saw the light for Italian nationhood and switched sides from the country’s Austrian occupiers. He was one of the first students to join the people of that city when they rose up to drive out their Austrian overlords and begin the First Italian War of Independence. The revolution of 1848 failed. After release from his first imprisonment, the zealous young convert to the cause di Rudio was repeatedly sent on ever more dangerous spy missions behind the Austrian lines by the revolution’s leader political leader, Mazzini.

Young and therefore invincible — and undoubtedly brave, seeing his face on wanted posters that read ‘dead or alive’ must have just added to di Rudio’s thrill of existence. Five years before the attempt on Napoleon III, after being caught by the Swiss police and offered the option of exile to Britain or America that he first saw England, — but he was soon back in Italy. After the Swiss caught him a second time, this time in Zurich they exiled him to Britain once again– where he arrived with just “sixpence in his pocket” in 1854. Working on the docks and in an Italian opera he lodged with an Anglo-Italian family where one of their relatives down in London from the north, was an illiterate Nottingham lace factory embroiderer of 16 (or probably 14), named Eliza Booth.

The tiny village of Godalming in England is a world away from the guillotine outside a Paris jail or the French penal colony of Devil’s Island, but it just a stop along the way in the remarkable life of di Rudio. In a manner of speaking, Godalming would save his life, though de Rudio did not contemplate as much when he married Eliza, his child bride there.

Dismiss from your mind any notion that the marriage was some sort of Green Card style transaction to stay in the country. The world did not work that way before the invention of the human rights industry – and it says much against the nowadays presumption that a man in his twenties has no rights to love a young person — mark this; the relationship had endured for a lifetime between Carlo and his Eliza, the mother of his six children, when Carlo died half a world away, aged 78.

In London with his skills in four languages he got some work as a translator for a French newspaper. All the while he hung out with fellow nationalists among the murky fraternity of spy versus spy, peopled by students, waiters, pimps, priests, labourers and crooks among the Italian community in London’s Soho.

The struggling revolutionary poor, de Rudio among them, often met at Signor Stucchi’s cafe on Rupert Street (beside today’s Chinatown, unless the PC police are these days calling Chinatown an ‘area of Asian heritage’). Stucchi’s was almost a pop-up — two leased rooms downstairs and one upstairs with a waitress, a waiter and a male cook. There, the firebrand revolutionaries argued and discussed interminably over the things that firebrand revolutionaries argue and discuss. On the night in question, a night in April 1856 — with the cook gone home, di Rudio came close to being killed in a knife attack by a shadowy figure named Foschini (who was never apprehended). Motives are unclear – the waiter (another intellectual simply doing the job to pay the rent) Ronelli had £5 on him as he was about to return to Italy – but almost certainly politics had a part in the mayhem. When the police arrived one man was dying and di Rudio was bleeding from multiple stab wounds.

After convalescing, he and his new wife returned to Nottingham where he gave language classes and Eliza got her old job back at the lace factory, until she gave birth to their first son, Hercules, in 1857. However the peripatetic de Rudios were back in London three weeks before Christmas that year. They moved into one room, third floor front of a tenement in a scruffy alley called Bateman’s Buildings just south of Soho Square. di Rudio had no work and had pawned his overcoat to keep food on the table. Little Eliza (by now a 17 year-old mother with a new baby) recalled that they were “in great distress”. Then a mysterious stranger began to call on di Rudio. The man turned out to be the Orsini plot’s banker, a French anti-Napoleonist, Simon Bernard, . He brought the di Rudios money, a passport and spoke in what Eliza called a foreign language to di Rudio. Eliza was instructed to buy a train ticket to go back up north by the 7:30am train the next morning and live under the name Booth. Carlo was on his way to France.

That brings us back to the Orsini plot which could so easily have taken Carlo from the world less than six months after his son’s arrival in it.

The reason given at the time for the French singling him out for a commuted sentence when he was possibly the guiltiest – after all, he had been not just a plotter with intent but an actual bomb thrower – was that Queen Victoria had interceded as di Rudio had an English wife. Now, call me cynical, but come on. One poor Nottingham illiterate lace worker whose foreign anarchist husband tried to kill a monarch does not merit a personal intercession via the diplomatic corps on behalf of a monarch who had a fair number of assassination attempts of her own to contend with. Another fact which seems strange on reflection is that Eliza, the poorest of the poor who had so recently been supporting the whole family on her tiny income each week could find enough money to travel to Paris – with her son — and to reside there during and after the trial, waiting to see her husband go to his death.

Isolated reports in the British press have di Rudio collapsing under the pressures of French interrogation and revealing everything of the conspiracy, though this story was later played down. What might be more plausible as a reason why he swapped the ‘short sharp shock’ for a ‘pestilential prison with a lifelong lock’ is that perfidious Albion had perhaps recruited young di Rudio.

But life rather than death was not a better prospect. He spent six months in prison in Toulon, where you can envisage how badly the failed assassin was treated and then two years on the complex of prisons and prison farms now collectively known as Devil’s Island, from December 1858. He and a nine others escaped by boat from the inescapable penal colony to British Guiana (now Guyana). Putting two and two together and making five, perhaps, just perhaps, the escape was even arranged or connived by the British, or indeed the French, to get back what the intelligence community now styles an ‘asset’.

By the summer of 1861 di Rudio was back in Britain, embarking on a lecture tour describing what he preferred to call his ‘tyrannicide’ to the few who would brave the British police’s close watch on attendees.

Coming next: de Rudio goes to America

1 comment

Comments are closed.