Entertainment before a big game is never as star-spangled as that at halftime, but organisers know you must not let the crowd get restive waiting for the main event. It was ever thus, though the acts may have changed a tad from those simpler times before twerking was a thing.

The big day in question was the official opening of the ‘new’ London Bridge — that day was August 1 1831.

Why new? Well, the new was replacing a bridge that had stood there for 600 and more years, making it worthy of the title ‘old’. That old bridge was wooden, blocked the river flow and had was so narrow under the weight of houses and shops built on it that it was worse than useless for traffic. It had once been a handy place to stick the traitors’ heads on a pole to discourage rebellions, but domestic strife was at such a low that the bridge had even outlived its usefulness as a rogue’s gallery.

This ‘new’ London Bridge was in its turn destined to become old and be replaced by an even newer bridge in the 1960s. Redundant as it was, it was exported to Arizona. For all its outlandishness as a concept, wrapped up in old world smugness about a dumb rich American who thought he’d bought Tower Bridge (which he didn’t) you have to admit London Bridge now looks mighty fine on McCulloch Blvd North, Lake Havasu City, but that’s another story.

We digress; back in August 1831 the new king but old man, William IV, was on his way down the river to do the honours. The old William was an interesting man. Never expecting to be king he had gone to sea, been a colleague of Admiral Nelson and had lived with his actress girlfriend for 20 years before they broke up, fathering five girls and five boys. Now he was in his sixties, married to a German princess named Adelaide and king for just a year.

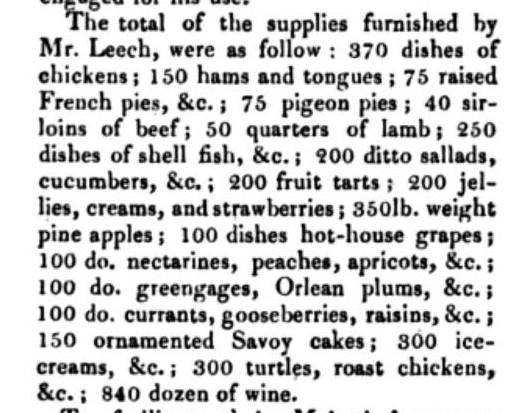

The royals were to be rowed downriver to walk across the bridge signifying it had been opened. But the king was not due until 4pm. The crowds began gathering from midday. Fifteen hundred of the City of London’s elite had been sitting down all afternoon in a marquee on the north end of the bridge to a banquet of vast proportions, but they had not forgotten the little people.

They hired two military bands, German singers offering an alpine chorus, a chap who did impersonations of musical instruments and whistled birdcalls, but culminating in the headline act, the great Boai.

Which brings me to the illustrious career of Michael Boai. Probably German, born in Mainz, Boai was a ‘chin chopper’. He was acknowledged to be the best from a long line of those who did what annoying schoolboys or deranged uncles do, that is to say tap on their cheeks while opening and closing their mouth to produce sounds of differing pitch. But unlike amateurs, Boai had perfect pitch over two and a half octaves and was said to be able to play extremely rapid passages of music with complete accuracy.

He was acknowledged to be very good at what he did: “Not only does he give simple airs upon this novel instrument, but the most difficult and complicated variations are executed him with perfect ease, every note even in the most rapid passages being distinctly marked.”

Another described Boai “executing the most rapid and difficult passages of some foreign airs with singular facility and precision; running up and down his scale, and marking even half notes with distinctness.”

Some of his contemporaries thought M Boai somewhat bizarre: “He has certainly the most singular mode of entertaining the world and maintaining himself that was ever conceived or heard of. The wonder is how his chin bears up against the thumps of The Merry Swiss Boy. Pugnacious Punch himself does not administer heartier whacks to the heads of his fellow-performers, than does Herr Michael Boai to his own.”

How loud would he have been to have satisfied audiences with his act? Pretty loud is the answer. After all he was regularly playing outdoors at venues such as the Vauxhall Gardens to crowds of people. Boai had toured northern Europe before arriving in Britain the previous year and straight off he played the Egyptian Hall. That was a sizeable room, a museum that had morphed into a lecture room and concert hall. When he played his chin he was accompanied by his wife on guitar along with a violinist as well, so he must have had volume enough to be heard above those instruments.

With practice he got even louder. By 1839 when he was appearing at the theatre in Brighton, the local rag had it that “he knocks the sound out of his chin with greater force than ever”. The ‘Chin Melodist’ also voiced the words of the songs he performed, though his broken English rendition of Rule Britannia as a finale was often more humorous than he intended.

The unreconstructed male chauvinist world all but forgot where the real talent in the Boai family lay. Madame Boai not only played the guitar and harp but could sing, in French and German and her voice was described as ‘pleasing’.

Though the Boais were still working in the mid 1840s before they disappeared from British records (probably retiring and going home to Germany), imitators had removed the uniqueness of Herr Boai’s chin music.

The one bright spot was that at last Mrs Boai was getting equal billing.

1 comment

Comments are closed.