There is a charming story to be found in the UK’s Daily Telegraph newspaper, though it’s a tad un-pc, as it reminds millennial snowflakes that all countries have had a past. A kind descendant has donated memorabilia of one of the first holders of the Victoria Cross. He was young lieutenant who had the guts (ignore the politics, admire the courage and comradeship, he was aged just 21), to ride his horse into grave danger simply to rescue another lieutenant. The story is here. I can say nothing about the rights and wrongs of a battle that took place in 1857, but what the story does not deal with is the fate of an entire collection of paintings of that band of brothers that held that highest military medal painted from life (for those who survived to receive the medal from Queen Victoria) that was a lifelong labour of one artist.

Among the kit of Lt John Grant Malcolmson, donated to the Army Museum is a full length portrait of the man himself. It was painted by the un-English sounding Chevalier Louis Desanges.

In fact Desanges was born in Kent, though of exiled aristocratic French stock. After studying in France and Spain, he began work in London in 1842. Success and he were not to be close friends. He failed to win the prize to decorate the new Houses of Parliament and the Royal Academy rejected the chance to exhibit his history paintings – including a now-lost work that was snappily titled The Excommunication of Robert, King of France and his Queen Berthe.

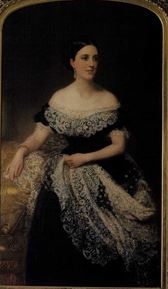

Whether it was his politics which upset the RA we do not know, but Chevalier Desanges had joined an organisation known as the Association for the Free Exhibition of Modern Art. Nevertheless, Desanges was no anarchist. He knew where his bread was buttered. He discovered that painting portraits of society ladies was an earner. While this may have paid the bills, it did not give him recognition. So he came up with the VC idea to gain him the prestige that seemed to elude him. This seems to have struck at least half a chord with the establishment. The Prince of Wales encouraged Desanges in the idea of the VC series, though it is said that HRH never dug his hand in his own royal pocket.

When Desanges had enough to make a show, the pictures were exhibited, first of all in the Egyptian Hall, in Piccadilly. Louis Desanges appears to have then worked exclusively on these pictures for the rest of his life. They were sentimentalised and sanitised battle scenes, where trusty British redcoats were seen bayoneting the swarthy natives or dying nobly, entreating on their comrades to further acts of colonial conquest.

By 1859, there were 20 canvasses, large and small, depicting Crimean War heroes. Later, after Desanges had painted a few more portraits of Indian Mutiny VCs, the collection was moved to the Crystal Palace, that was, by then, in 1862, under private ownership and had been three years at its site in Sydenham.

A sad footnote was the fate of those “mediocre” VC paintings that the artist Desanges painted to curry favour with the establishment. There was a half-hearted attempt to get together enough money to save them for the nation, and to put them into a purpose-built gallery. That failed.

A small ad appeared in the classified section of London newspapers. They could be purchased, together or separately. All one had to do was contact Charles Wentworth Wass at the Crystal Palace.

It was left to one of the VC’s himself to buy them. Robert James Loyd-Lindsay, Baron Wantage VC KCB, was one of those 62 VC’s in Hyde Park in 1857 at the very first investiture. Queen Victoria leant from the saddle of her horse to pin her medal on each of these undoubtedly brave men, officers from high caste families and humble working men, assembled shoulder to shoulder on that meadow. As plain Robert James Lindsay, then a captain in the Scots Fusilier Guards, Baron Wantage had accomplished that quintessentially Victorian act of bravery. He had persuaded his soldiery to defend the colours against numerically superior opposition at the battle of the Alma.

Wantage had married into a fortune. He now purchased the paintings for £1,000, including the rendering in oils of his own heroic action. In November 1900 he gave them to the people of the small Oxfordshire town of Wantage ( whose unintentionally ambiguous motto is A Place to Live, A Place to Love) where he set up home. He gave them in perpetuity as a memorial gift, expending more money than the paintings cost on proper gas lighting and heating for the building selected to house them, next to the Bear Pub on the Market Square. The town of Wantage responded almost as gallantly, spending all of £3 to have the name Corn Exchange chiseled out of the frontage of the Corn Exchange, where corn was conspicuously no longer exchanged, and to re-work the words, The Victoria Cross Gallery in their stead. (It’s now a Greggs, a chain bakery store, by the way.)

For 40 years the paintings were on view to the people of the little town on payment of threepence (children, dogs and bicycles not admitted). The paintings seemed to have survived numerous tribulations during their time in Wantage. The local badminton club and officer cadets from various schools used the hall where they were hung. The paintings got through the First War, during which the room became a makeshift military hospital. But during the Second World War in 1941, just when the good folks of Wantage might have needed a little morale boost by visiting the scenes of previous brave men, the Ministry of Food thought that the VC room would make an ideal site for an emergency kitchen to supply meals to the children of Berkshire. The paintings were packed off to a leaky lean-to shed at a local engineering works.

When they finally came back in 1951 some paintings were damaged beyond repair. Despite an intervention by the wife of the poet and Victorianist John Betjeman on instruction from her husband to try to retain the paintings in the town and re-hang them as a group, the post-war councillors wanted nothing more to do with the Victorian anachronism of the nobility of war. They quietly disposed of their gift from their local hero and the town’s namesake, by now long dead and without children to pick up the baronetcy title.

Somewhat surreptitiously, the council wrote to each regiment that could lay claim to any of the VCs, enquiring whether they had room to display their long-dead imperial hero. During the 1970s the council gave away paintings to other than those military institutions which might have had at least a moral claim on them, it is said. “The circumstances in which this occurred have still to be investigated” says a local historian. At this time no-one knows quite where all the pictures are, whether the council had the right to even give them away, who is entitled to claim ownership or even how many survive. At least the borough kept the painting of Wantage’s favourite son and benefactor, and it now hangs in the Civic Hall.