Eupion Oil is slippery stuff. It’s one of many hydrocarbons bearing classical sounding names that they could so easily be diaphanously-clad minor spirits partying with old Zeus disguised as a bull. Not wishing to sound like a Tom Lehrer tribute band, but aside from Eupion there’s kerosene, naphtha, propane and toluene. Ethane, methane, heptyne and undecene, Classical allusions point to the fact that many of these compounds were first identified in the earlier decades of the 19th century when science was still a branch of the arts and scientists knew their Latin and Greek.

But hey, class, we’re here to talk of Eupion. Since the 1850s Eupion was used for many disparate purposes; to protect telegraph wires, as a domestic stain remover without the ominous ether-like scent of operations and as a substitute liquid to light lamps in place of the ever scarcer and pricier oil from lately deceased whales.

Then in the early 1870s a German living in London developed a patented process, which, if it worked as claimed, could easily turn the liquid into a gas that burned twice as bright as coal gas. And it could be piped across towns and into homes. It could also serve as a smoke-free alternative to coal for the steam engines propelling London’s Underground. More especially though, the Eupion could be transported as liquid to serve new weeny domestic micro-gasworks that would light isolated communities or even country houses where the expense of running pipes to them was too great. Hurrah for the Victorians and their constant striving for new technology to drive forward civilisation.

The way to capitalise such technology of course was through floating a company.

So this brings us on to the Eupion Fuel and Gas Company and some slippery customers who first met their accusers in late 1874. It turned out that during that year these minor league City crooks aiming to go up to the bigs had been selling their shares through stupidly innocent share dealers over and over again to their mates. The accomplices then gave the shares back to the directors and then went and bought some more. This was to make it seem like the world was interested in Eupion.

The money too was recycled. Sloppy auditing and a dodgy bank manager meant that the Eupion board would pay the proceeds into one bank, then tell the first bank that they were transferring the cash to the equivalent of a high interest savings account at another bank whose dodgy manager ‘loaned’ the money straight back to the directors, The directors passed it straight to the accomplices so that they had the cash to be able to buy more shares. Unaccountably (literally and metaphorically) the innocent first bank told the Stock Exchange that all the individual payments of the same money which it had seen repeatedly come and go across their counters still added up to a grand total. This pleased the Stock Exchange, which would not let a company be entered as a publicly traded stock unless a majority percentage of its shares had already been privately taken up.

Another nicety of the Stock Exchange was that it signed off on a new issue by naming a ‘settling day’. Upon that future day the brokers who had bought on behalf of clients had to pony up the cash and the Stock Exchange dealer who had sold on the understanding that he would have the shares come settling day had to provide the promised Share Certificates. If he did not have the shares he would have to obtain them — at any price. In any rapidly rising market it could be impossible to get even one hot share as everyone was hunting the same stock. And if the dealer failed to come up with the goods and the deal was held over to the next settling day, then the buyer’s broker could exact what they called ‘blood money’, the difference in price between what the agreed to pay for the shares and the actual cost of obtaining them – and it was no small amount.

But of course all the ‘sold’ shares had never left the oily hands of the Eupion directors. So they held them back so that all their phoney buyers could claim their blood money.

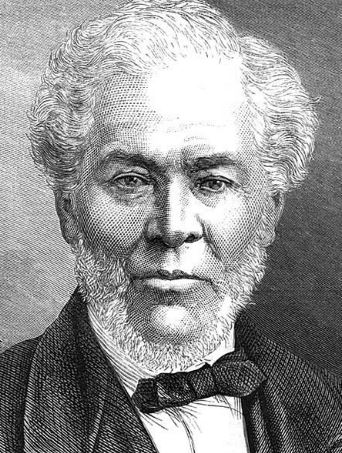

Ingenious though the fraud was, the Stock Exchange and the trial judge, an ex-Lord Mayor of London and Calvinist Scot grocer named Sir Andrew Lusk were onto the wheeze.

This was, after all, so much more important than a fraud against any old shareholders. No, it was far worse to Lusk and his City contemporaries; it was a fraud against The Stock Exchange – that meant and attack on the smooth operation of capitalism itself. The Stock Exchange was stung by this clever intrusion into the well-oiled relations of buyer and seller. Knowing it could not act itself, it forced the dealers themselves to call to account these half a dozen ‘respectable’ City figures who had conspired to go just too far.

This buying and selling of shares that you did not hold was indeed a part of a system that itself by its nature condoned – no, encouraged Much of this sort of gambling and market rigging was ‘honest speculation’. It was how brokers and dealers earned much more than the money their simple commission would pull in. Cornering a market, bulls, bears, shorting and all the other tricks of the trade were acceptable, naturally, but this was not. The Eupion directors had invented a way of doing business quite as dishonest as many others, but this was not one that was sanctioned.

In their various defences, the prominent names who had become Eupion directors did the unthinkable and bit at the hand that hitherto fed them — and not just the Stock Exchange itself, but to those colleagues, friends and enemies who right now filled the crowded public spaces of the courtroom. In his defence one accused argued “…the Exchange said the morality was to buy what they could never get and sell what they could not deliver”, and he was right. That did not go down well with the rest of the club. No-one likes a cheat who tells teacher that there others were cheating, so it was off to the Old Bailey for the half dozen in the dock to face criminal proceedings for fraud.

The Central Criminal Court, to give it its proper title, dealt with murders, assaults, theft and burglaries – interpersonal offences — and so this bit of white collar crime was quickly shuffled back to the Queen’s Bench a court which was finding its feet following the wholesale revision of the British court system the previous year. Though justice always proceeded with glacial sloth in Victoria’s age, they seem to have been particularly snowed under as it did not come to court for two whole years. So it was back to the courtroom in the Guildhall, but this time facing the Lord Chief Justice.

The fraud charge was difficult to prosecute. Who had defrauded whom? They weren’t the first in the Square Mile to hold onto shares to push for blood money. The shares they sold were actually sold in the way that shares should be sold. Yes it’s true the bank manager was conspiring to give the money back as a loan, but hey, it would not have been the first dodgy loan, nor the last and that in any event was for the bank to prosecute. Yes it’s true that the buyers signed the shares back to the company, but that too was broadly legal.

The jury took just 40 minutes to say they were not guilty of the more serious charge conspiracy to defraud. However they were guilty of inducing the Stock Exchange to grant a settling day by false pretences – though no-one including the judge knew if this was actually a crime at all.

The court was “very much crowded” on Saturday morning July 1st 1876, when the accused were finally called back to face sentence. But first came the pleas in mitigation. One claimed that he had two life threatening diseases, 12 children and aged parents to support and who would be condemned to the workhouse – he got 12 months. Another claimed that he had only become roped in as a trustee of the estate of one of the patentees – he got two months. The bank manager for 30 years who was on a salary of £1200 a year with a promotion in the offing till this blew up – he got 12 months.

The lesson, of course was to others in the City. Keep to the rules and do not try to invent new ways to screw the system. There were enough schemes to do that in place and the system did not need any more.