If you recently ate a meal that you’d rather not see back again, look away now. I say that because we are about to closely examine the festering old wound of Italian resistance partisan Giuseppe Garibaldi. The look-see at what this poor man went through says a lot about the stoicism of our forebears facing the dire risks that any infection brought with it. It says much of the state of treatment one could expect if you suffered an injury in Civil War times. It says most about the lack of decorum and privacy of public figures when the people felt it had need to know about their designated hitters.

The battle beside an Italian mountain known as Aspromonte took place on August 29 1862. It barely lasted 15 minutes. It came to an end after just a few volleys, as neither side really wanted a fight. In the end around 12-15 died. On one side was a regiment of General Giuseppe Garibaldi’s red shirt volunteers heading north up the Calabrian boot of Italy from Sicily, metaphorically clutching to their collective bosom the slogan Roma o morte (Rome or death) and the intention to kick the Pope out of his very temporal domination of the capital. Opposing them was the black feather-hatted Bersaglieri corps of the Royal Army of King Victor Emmanuel.

However, as the Italian nursery rhyme about the indecisive little skirmish goes, Garibaldi fu ferito; Garibaldi was wounded. And he was. While running along in front of his men ordering them not to fire on brother Italians, he was hit, twice.

If like me you thought that “If it bleeds, it leads” was a maxim descriptive of TV newsrooms since the Vietnam War, think again. Yes I know there are some Civil War corpse photographs, though by the tightness of their shirts, the dead in them have been that way for a day or so. The darling of Europe’s intelligentsia and the hero of the common man, Garibaldi, was shot twice; once in the thigh and the again in the notoriously slow-to-heal heel, but for the readers of the world’s newspapers, simply knowing that was not enough. Papers from as far away as Australia spent months reporting the will-he, won’t he die accounts of his recuperation.

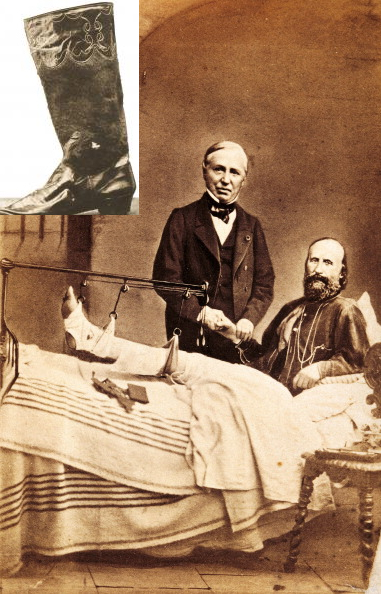

As the battle was brief and the partisans surrendered, Garibaldi got prompt medical treatment from an army surgeon for a laceration to his left thigh and a more serious hole in the right ankle. The heel wound was no better by September and people gloomily began to hint at amputation or worse, that it may have “fatal issue”. He was by now weak, feverish and in pain. The biggest question was whether the bullet – and we are talking of one of those conical Minié type rounds weighing more than an ounce – was still buried inside the joint where the leg bones meet the foot. X-Rays are a wonderful thing, but it would be nearly 40 years before they were discovered and just a few years after used in hospitals. So finding out was going to be done the old fashioned way, as we shall see.

Garibaldi was almost a Nelson Mandela figure to armchair champions of liberty, so every sawbones wanted a piece of the surgical action. Foreigners joined doctors from all parts of Italy and congregated where Garibaldi rested in a first floor room with taped up windows. The British entrant in the European Find the Bullet competition was Professor Richard Partridge. Though an A lister, he had no experience of gunshot wounds. Still he was big in the medical establishment and destined to become president of the British Royal College of Surgeons in a few years.

With Godlike conviction Partridge told the world that there was no bullet in Garibaldi’s ankle. With that scientific arrogance — certainty delivered in the absence of knowledge — he pronounced that Garibaldi would make a full recovery. He collected his fee from British well-wishers and went home.

By late October though, the humbled Partridge was forced to retrace his steps across Europe. Those ‘inferior’ Italian doctors claimed the leg was plainly not healing because there really was a bullet embedded deep against the bone.

So an international surgical seminar was called in the sick room. They came from as far away as Russia, though at least Russian Professor Pirogov’s pioneering work with injured men during the recent Crimean War gave his some real experience of bullet wounds.

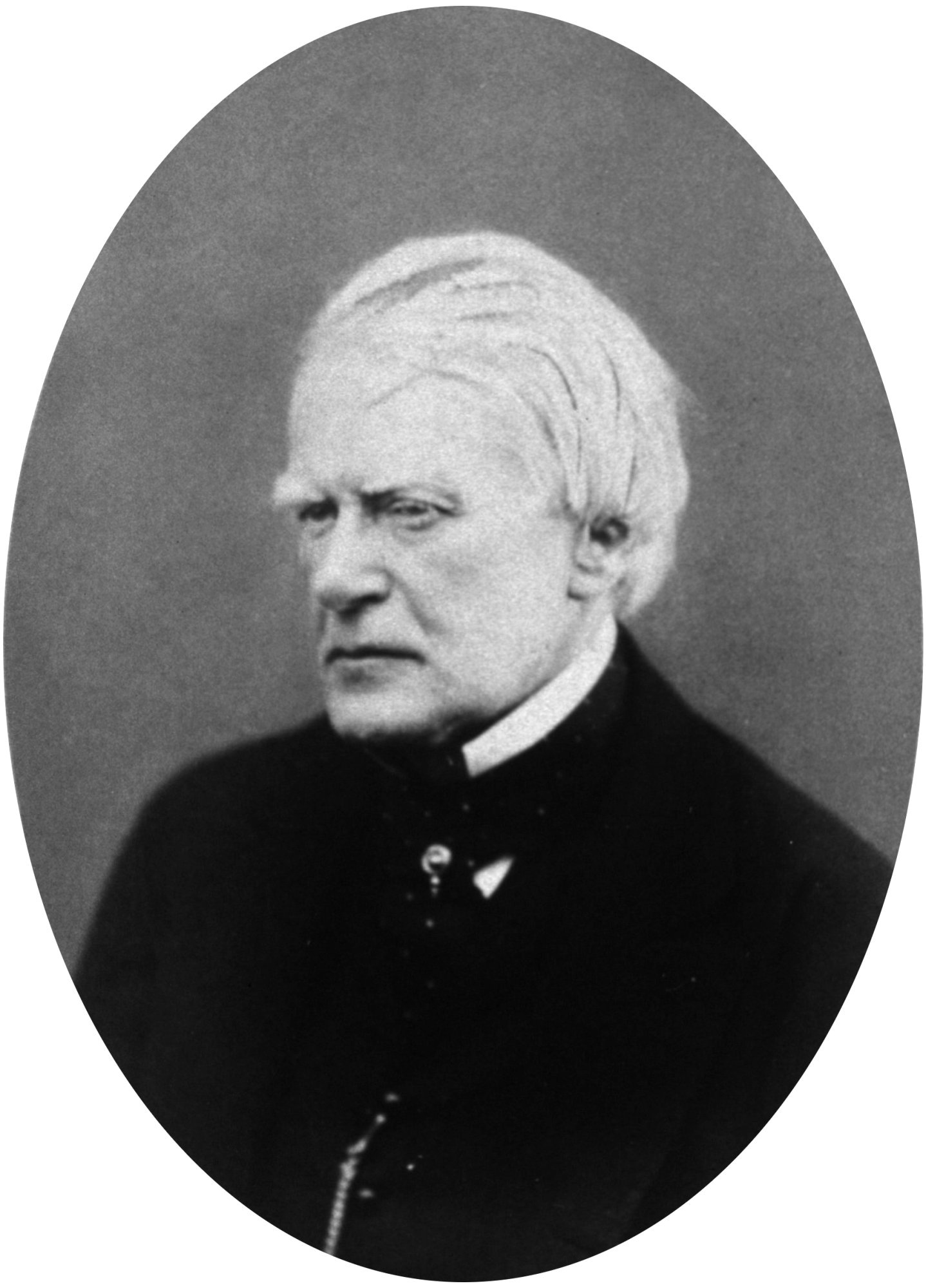

Pirogov (left) said there was a bullet, as did a French surgeon named Auguste Nélaton (right). Partridge was adamant that he was correct first time. Altogether 17 doctors at various times gathered at Garibaldi’s bedside and opinions were, shall we say divided. What Garibaldi made of all this goes unreported, but it is worth a glance, wincing for him from behind the couch, at what he endured for them to come to this inconclusion:-

Nélaton thought about the problem of locating a hard object (the bullet) hidden among the crevices of the shattered bones of Garibaldi’s ankle and in a moment worth celebrating he devised an instrument that was cheap, easy to use, portable and which worked to determine where a bullet was. It was so simple. On the end of a probe he put an unglazed ceramic ball. Pushed against bone, no mark. Pushed against a soft lead slug it left a discernable grey smear.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Three years later, in the early morning of April 15 1865 a world away, the Nélaton probe was pursuing its path through another famous wound, but this time the patient was already beyond saving. That patient? President Abraham Lincoln.