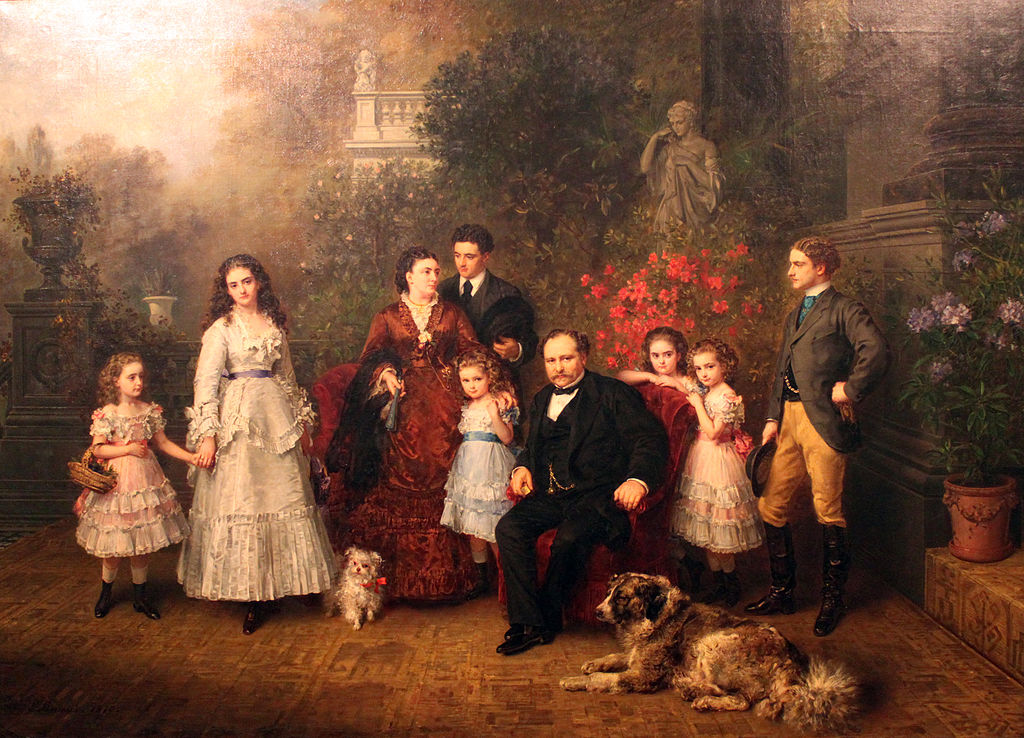

In a Berlin art museum there is a portrait of a family assembled around a rotund, modest-looking little German man.

He is uncomfortably seated, apparently shifting his weight. Standing about him is are his English wife, his sons, daughters and even the family dogs. He could be a successful local burgher, but no, he is der Eisenbahnkönig — the railway king of the Fatherland. The palatial modern town house in which they sat to be painted he had built for his family in one of Berlin’s highest class streets, Wilhelmstrasse, opposite the Brandenburg Gate. Just one of its claims was that it was the first private house in Germany that had its own indoor swimming pool. The Berlin mansion was so imposing that in 1877 it fell into the hands of the British government which made it into the Embassy. It is just one of many palaces and estates he owns. He was that wealthy.

It is 1870. That balding, tubby gentleman in the picture employs 100,000 people — and though he does not show it, save for the gold watch and chain, he must be among the richest in all Germany. Hold that thought for a minute and travel back 25 years.

At 7 am on July 10th 1847 a new-built American paddle steamer Washington was towed into Southampton Water for its return voyage from England to New York. The Washington was, to use the words of The Times‘ shipping correspondent who observed her, “about as ugly a specimen of steam-ship building as ever went through this anchorage”.

At 4pm, with the last mail on board, she departed. By late that night she was 100 miles away down the English Channel when a problem arose. Stokers discovered that the English anthracite coal was burning so hot that it was melting the grates. With engine trouble and facing a journey of 3,000 miles, that signaled a return to port. It was to be the undoing of one of its passengers. That young man must have been feeling pretty comfortable that Saturday evening as the Washington paddle wheels thrashed further and further along the southern coast of England, soon to leave sight of any land behind. That man had been in something of a hurry to reach a country where the living would be easy and extradition back to the UK was hard.

He was named Bethel Henry Strousberg. Yes, he was indeed the brother of Ferdinand Philip and he was on the run. The week before he paid £30 for a ticket to New York in the name of Bartholde, but it was he who boarded the ship.

It was so out of character. Young Strousberg had worked incredibly diligently since he arrived in Britain, aged 16, some eight years before. Baruch, as he was then named, a fourth child, had been left impoverished when the meagre family inheritance back in Prussian controlled Poland was divided after the sudden death of his father. Baruch was shipped off to stay in England with his three uncles who ran a successful importing business. He got his first sight of London when he disembarked from the Sirene on September 27th 1839. He lodged with his uncle Peter in Newgate Street. There he was persuaded to take his new name Bethel and learn all he could about finance, markets and moneymaking. He stayed there until Bethel did the unthinkable act that severed the connection forever.

At least that must have been the way that his uncle, Peter-Moyses, saw it. Bethel repaid all the hospitality he received from his close family with a kick in the tukus. What Bethel did was to abandon the Jewish religion of his ancestors. Bethel converted to Christianity. And on March 13 1845 he married a scandalously young 16 year old named Mary Ann Swan, the daughter of a linen draper – in St Bride’s Church in Fleet St.

As far as the older generation of the family were concerned Bethel was dead. They were religious, part of the growing reform movement. Their late father, Bethel’s maternal grandfather, had been a rabbi back in Prussia and “lived a life dedicated to God alone”; so much so that when the old man died in his nineties it was on his daily journey back from the synagogue. The black cloths over the mirrors in Newgate Street would have marked the seven days of shiva for the dead – or in this case the otherwise departed forever from their lives.

Three months after his marriage in July 1845 Bethel suffered his first financial reverse, when he was made an insolvent debtor. Under the harsh regime of the day, that accident of dropping the ball while financial juggling meant spending a couple of weeks in prison while Strousberg waited for the seedy insolvency court where the London School of Economics now stands to hand his debt over to an assignee who would sell any assets Strousberg could lay hands on. That seemed to have worked for by the next year, 1846, the year before his attempted escape on board the Washington, Strousberg was discharged from insolvency.

Within that year he progressed from a somewhat lowly and disreputable job as commission agent, a money lender cum debt collector. Now relying on his salesmanship and ways with money he was fronting the launch of a number of embryo building societies. Known as building clubs, they were a cross between a lottery and investment and loan company. They catered for working people for them to get to buy their own houses or to invest their small savings in order to get a return.

The Times Building and Investment company was one such and the Fifty Pound Building Club was another. When the Times took out a launch advertisement the society was proud to announce that Strousberg was the man who had calculated the actuarial table on which the society would rely. You’re ahead of me if you think there is a whiff of embezzlement coming up in this story. But against some of the earlier tales of gross and cynical corruption, Bethel’s embezzlement was both tiny and inexplicable.

We do not now all the facts, but it seems Strousberg went missing at work, though it is not clear how anyone was able to find out that he was leaving the country and for that matter by which port or which ship, but you have to suspect that his wife may have known something of his plans. For though he was leaving her, he was not abandoning her. In any event a senior man from the Building Society went down from London to Southampton on the train to have him arrested. When he got to the port he first thought he was too late — but you can imagine his glee as the ugly Washington trundled back into port. Strousberg was hauled off the ship to face criminal charges for not banking £7 and 17 shillings for the Times Building Society that a member gave to him on July 6.

The officious, ludicrously named magistrate, Hughes Hughes, sat at London’s Guildhall magistrates because he was an alderman of the City of London. He had previously been an MP, but was it was noted in his obituary that in the unofficial directory of the House of Commons his name was mentioned in a passage devoted to ‘Unpopular Members’.

Strousberg had a defence, though it was a subtle one — too subtle for Hughes Hughes. Strousberg protested that the building society was only allowed under the regulations to have just one paying-in day a month. Until that day came around he was just holding the money, not on behalf of the society, but on behalf of the man who gave it to him.

“Aha” said Hughes Hughes, “you were sailing to New York and so you could not have been able to pay it in when the time came due”. He was remanded until later that week, as the Fifty Pound society had chimed in saying that £19 was missing from their accounts too. By the end of July when he was back in the dock again, things at first looked up. Both building societies had decided not to press charges, principally for the lawyer costs involved. Unfortunately though for Strousberg, both building societies had taken a precaution to re-insure any losses with an insurer, The General Guarantee Company. Rather than see Strousberg’s release prompt a string of copycat cases, General Guarantee wanted to see Strousberg made an example of. So did Hughes Hughes.

The charge carried a penalty of repayment of twice the amount owed, or three months in jail. Strousberg’s solicitor pleaded for more time for the defendant to find the cash to pay back the fine. No-one in England was able to go surety for him but he had reached out to family and friends back in Germany. The newspapers reported that he got the fine and as he could not pay was committed to jail.

Here the reporting goes cold. Did he break rocks for three months in 1847? Did the money come through from Germany and satisfy the court so that he did not have to spend endless hours hooded and climbing steps in a silent prison treadmill? We don’t know. However it says something about the Victorian idyll of redemption that a one-time bankrupt such as he should have been given a second chance to manage financial organisations. And on the face of it he repaid the offer of forgiveness with embezzlement.

But a third chance? Let’s put it this way. There must have been something magnetically charming about this young man and for that matter his brother too; that and the fact that Bethel appears to have been something of a mathematical genius. Six years go by and when he next surfaces on the record, he has become a business magazine owner/editor and so much of an actuarial whizz that he is listed as consultant actuary and manager to at least two life assurance companies. He published a highly commended pamphlet remonstrating with government, warning it of the near monopoly of old-established firms in the life assurance business which aiming to squeeze out new entrants. So popular was the document that by October 1852 it was in its second edition.

And though a convicted felon he was unafraid to do the almost unthinkable — call the law an ass in general and especially berate one particular magistrate — to his face. Not that he was a defendant or even a witness in any case, he was so angry in March 1854 over what a judge had said that he just turned up at Bow St Magistrate’s Court asked for and was granted a public forum to tell the judge his opinion was biased and wrong. He got his day in court because on the previous Saturday his Honour Justice Jardine — or ‘In-justice’ Jardine as he was widely known, for dispensing very much softer sentences to the rich than the poor — had been giving his own advice from the bench.

The previous week Jardine had let two “decently dressed Irishwomen” come to court in what appears to be a put-up job to discredit Strousberg’s Oak Life Assurance. They complained that the poor and illiterate were being seduced into buying life assurance policies. There was no case but they were allowed to ask his advice in a pointed question about this state of affairs. This allowed the judge to make a speech in which he roundly condemned new building societies, especially the Oak. Jardine looked over the papers they brought and hurrumphed that while the Oak appeared to be genuine, he did not know the names of any of the directors. Jardine was of the opinion that “the practice of sending agents among these poor ignorant people… was a very extraordinary one, to say the least of it.”

The following week Strousberg demanded that Jardine retract his comments, for what he had said had a “very injurious effect upon the society” and claimed that 100 people had turned up at the Oak offices, asking for their money back. His Oak Assurance had simply replaced the unofficial and unregulated ‘Burial Clubs’. His directors were “among the first merchants in the City”.

The judge was not about to back down in his own court. “I still adhere to the opinions I expressed.” Using all the understatement available to the reporter, Strousberg’s reply to Jardine was said to be deliver “with warmth”. The angry Strousberg told the judge: “With every desire to be respectful, I wish it to go forth that I think a magistrate’s function is to decided upon facts, and not to give opinions.”

Not getting, or not waiting for an answer. Strousberg walked out.

And Henry Bethel? He went back to Germany to become that comfortably tubby, multi-millionaire family man in the portrait.

In Germany he went on to launch companies worth £100 million, employ upwards of 100,000 people making the steel and building the rails that carpeted Eastern Europe in a network of railways. He invented for himself the Trust, the vertically integrated industrial system that garnered profits from owning all the means of production in his industry. He owned the mines that provided the coal for the steelworks that made the rails and raw materials for his engines to run on his railways. He owned the railroads and even ran the vegetable markets and abbatoirs that relied on his lines.

But his was a journey to monopoly based on necessity. He started his railway engine works to ease his company from price gouging from Germany’s sole engine maker. In doing so he brought efficiency such that he introduced the production line concept to manufacturing some 50 years before Henry Ford re-invented it. Sadly the “European Railway King” had a final descent almost as precipitate as his fall from grace in 1847, but that’s another story…