More real life from the 1880s as told to readers of the Little Cyclopedia of Common Things, (see a previous post for more about the book), brought to you this time by the letter P. Every one a winner for historical novelists.

First up is a listing for Paint. There wasn’t much in paint then that wasn’t toxic. Black and white, red and yellow paint each had lead compounds as their major constituent, while vermillion had mercury and green had the poisonous copper compund known as verdigris in it.

In the entry for Pickles; after explanations of how to pickle and what to pickle comes this note of caution, again about the colour green: “Makers of pickles often boil their vinegar in copper or brass kettles, which gives the pickles a rich green colour; but this should never be done, as the vinegar forms an acetate of copper which is very poisonous. Therefore pickles of a brighter green colour than the vegetables themselves should never be eaten.”

A 19th century murder mystery writer’s McGuffin right there, I think.

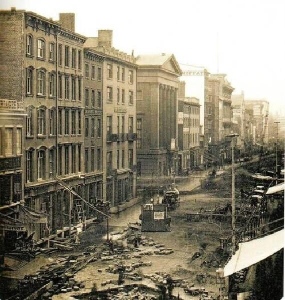

Less life-threatening is the entry for Pavement. The listing is copious in its detail. This word is used in the American sense for road surface, rather than in the present day English meaning which is translated as sidewalk. As it says in its opening remarks: “In streets where there is much traffic great care must be taken to have a good pavement.” It then lists the options which were commonly used in towns and analyses their strengths and weaknesses. Wood blocks, good but tend to get slippery and rot; bricks, wear out under iron shod wagon wheels; iron block, noisy; cobbles, good grip for horses, but tend to come unstuck and need constant maintenance.

The book concludes that stone setts are best — and then goes on to list three rival kinds of stone pavement regime — the Russ, the Belgian and the Guidet, though it fails to differentiate them.

Pavementologists with time on their hands and historical novelists intent on further period details need look no further for more details than A Treatise on Roads and Pavements by Ira Osborn Baker in 1903. ‘The earliest dressed stone-block pavement in this country was the Russ patent laid on Broadway, New York City, in 1849. This consisted of a 6-inch natural-cement concrete foundation on which was laid rectangular granite blocks, 10 to 18 inches long, 5 to 12 inches wide, and 10 inches deep, the sides of the blocks making an angle of 45 degrees with the line of the street. The Belgian block was introduced in this country about 1850, and for a time was much employed. The Guidet pavement consisted of stone blocks having a hexagonal top surface, the joints running perpen dicular to the street being comparatively wide and those parallel with it being comparatively narrow. About 1869 a considerable amount of this pavement was laid in New York city and Brooklyn, at a cost of about $7.00 per square yard. So now you know.

Phonographs, Photographs and Pianofortes all get a mention as one would expect, but artisans’ tools such as Pincers and Planes come in for extensive examination.

Phonographs, Photographs and Pianofortes all get a mention as one would expect, but artisans’ tools such as Pincers and Planes come in for extensive examination.

Pigeons, which might get a brief mention under ‘birds’ in a similar book these days, got three whole pages. There is no hint in the description that the then still astoundingly common Passenger Pigeon of North America, so plentiful that “they sometimes fly in such vast flocks that they hide the sun and the noise of their wings is like the roar of the wind” would be gone from the wild in just 20 years. A boy in Ohio shot the last wild one in 1900 and here it is, the Norwegian Blue of the pigeon world.