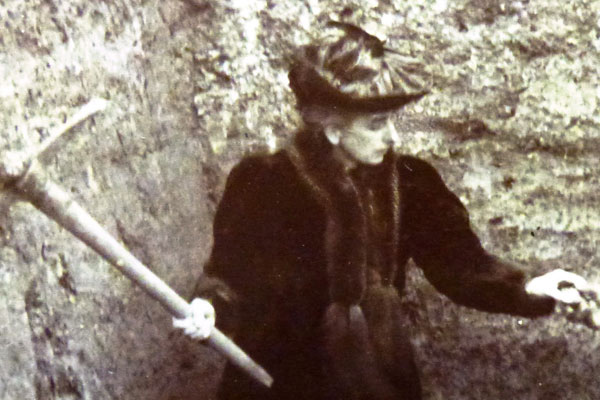

There aren’t many practical archaeologists who are also published poets. Let us celebrate the life of Nina Frances Layard (1853-1935).

She was the first elected woman Fellow of the Society Antiquaries. She was a foundation member (and President 1922-23) of the Prehistoric Society of East Anglia, and was practical archaeologist and excavator. Most of all perhaps she was a feminist before the term slipped into self-reverence.

Hers was an age when it was easy to denigrate a person for being the gender she was and for shaming her on faults, if faults they were, that would never have been publicly described if it were a man the commentator was criticising. Here are some examples – and note the reference to her father in the first. As if somehow he was something more a puppeteer than a relation.

First a review of an early book of Nina Layard’s poems.

“Readers who have a taste for real poetry will be pleased to have their attention directed to small volume which the above publishers have recently issued, for we are quite sure its perusal will give them gratification. The fact that Miss Nina (who, by the way, the daughter of the Rev. C. C. Layard, whom the book is dedicated) is the author these thought-laden and graceful compositions may surprise some who only heard of her as a disputant at the recent meeting of the British Association, where she challenged the Darwinian hypothesis in its bearing on the question of reversion. That the controversialist, dealing with this obscure physiological theme, should possess the poetic temperament is what few would have suspected. By a rough and ready mode of generalisation we conclude that taste for the dry details of science must be incompatible with the sensitiveness and “fine frenzy” characteristic of the children of song.”

This is what actually happened at that British Association meeting referred to. It was held in Leeds in 1890. There was only one other woman deigned expert enough to present a paper, but that woman was not brave enough to read it herself. She gave it to a man to read for her. Not so Miss Layard. (And note the references to her appearance).

“The lady read her own paper and the appearance on the platform of a smart, clean cut, dark-complexioned woman, dressed in black, as the signal for the hearty applause of the audience. The paper gave rise to a most animated discussion, many clergymen and gentlemen taking the part of Miss Layard very strongly”

Liverpool Echo 6 Sept 1890

Not so convinced was man from the Edinburgh Evening News. Its reporter was scathing, listing her paper and one other (from a man) as “clotted nonsense” that were likely to bring ridicule on the whole proceedings. Good for Nina Layard though, for when the chairman interrupted during her speech and told her that she was not up to date with the research on her particular topic, that of atavism or reversion in humans, she simply continued her thesis. As the paper said patronisingly: “Miss Layard, however, woman-like declined to be convinced and declared with a delightful want of logic, that if the doctrine of the evolutionists were to be accepted, the man with down on his skin must be regarded as the ancestor of the ape with the coat of hair.” She was making a serious point about the social Darwinian notion of atavism and was challenging it with the “which came first” example of skin hair in humans and animals.

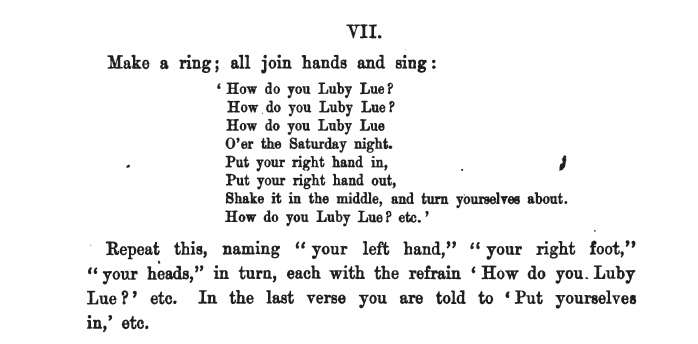

So, poet and archaeologist. Her career-long studies in neothlithic stone tools contributed greatly to the pool of knowledge of her time. Add to the mix social anthropologist too. Her recording of children’s games and play songs in the East Anglian region of England where she lived all her adult life is a vital record in the same way that Ralph Vaughan Williams and Cecil Sharp’s folk song collecting saved another part of the disappearing heritage.

It was inevitable that when her lifelong friend and live-in companion, illustrator Mary Outram died in June 1935 that Nina would soon follow. The obituary says she died ‘following an operation’ and it is notable that she could not attend Mary’s funeral, whether through ill health or a misplaced Victorian sense of place we will not know. Nina died in August 1935, aged 82 and was buried with Mary in the same grave, still flower-covered.

Here’s a poem that got wide coverage on both sides of the Atlantic. It may not be her best, but it’s one to remember a pioneer by.

Sad Evening Primrose, with your silken stole

Hung delicately sunward, what a soul

Looks from your patient eye! How frail and pale

You stand among the flowerets and your bowl

Shows like a vanishing phantom of the grail

Young buds that point a finger to the blue

Crowd on your stem, and youth and hope are new.

While the sap runs; yet scarcely has the sun

Warmed twice upon your petals ere their hue

Fall into pallidness of death begun.

And strewn about the grass the blossoms hide

The poor discoloured fragment of their pride.

Or hang disconsolate with draggled vest.

And clinging, sodden cerements, to abide

The gradual workings of the Alkahest.

Was it for this you struggled into light?

That one brief day should crown a tedious night?

Was it for this you felt your way along

The paths of natural growth, that from their height

Shrill death should echo in your triumph song?

It may be so. There are who say the bliss

Requites the pain: yet could it be for this

(God knows) you opened your sweet, patient eye

To see the sun’s face once and die in his kiss?

For me you bloom again in Paradise.