If that was how it was at the Cremorne, what could things be like at the Royal Aquarium in London’s Westminster district? How was a room full of fish tanks a threat to morals?

Just a glance on a map will provide part of the answer. The Aquarium was in Tothill Street, Westminster. It was less than 100 yards from Parliament Square, the House of Commons and Westminster Abbey. Vice and licentiousness might be tolerated in the poorer districts of the East End or Islington, but not within earshot of the governors temporal and spiritual.

The Aquarium was a stone and masonry public hall opened in 1876. It had its own barrel vaulted iron and glass roof as homage to the Crystal Palace running the length of its 340 foot great hall. The main room was filled up with palms and other hothouse plants, along with classical statuary, while the promoters boasted that “between these groves fountains will play”.

Around the walls were 13 giant tanks for the fish. and under the floor were asphalt- and vulcanite-lined storage tanks for a total of 700,000 gallons of sea and fresh water. Not only was it to be an Aquarium, but it aimed to be a home away from home for visitors. It had a reading room with English and foreign papers, a telegraph office, cigar shop and offered even a division bell so that MPs relaxing beside the fish tanks could return to cast their votes in the House when needed.

It had its own tame royal in the shape of the Duke of Edinburgh to cut the ribbon. In addition, the organisers had roped in some other big names, with Sir Arthur Sullivan in charge of the music and “Mr Millais” in charge of the picture selection. What could possibly go wrong?

The only thing the Aquarium lacked when it opened were fish. As Charles Dickens junior put it in his Dickens’ Dictionary of London in 1879: “Unfortunately the desire of the directors to obtain an immediate return for the large sums invested in the undertaking unduly precipitated the beginning of the campaign. Not only were the plans of the managers in an inchoate state, but the tanks without fish became a standing joke, and the dissension which arose among the discontented proprietors further tended to create distrust of the enterprise in the public mind. After some time, the tanks were filled and energetic management provided attractive entertainments of a superior music hall type.”

That was the nub of the problem for the public order police. To revive their investment the owners made sure the hall became popular — in both senses of the word. This rapid move down the social scale improved its fortunes but lowered its image. No longer relying on the casual visits from MPs, the owners marketed the theatrical annexe to the complex to attract the music hall audience. Shows featuring Nat Emmett’s Wonderful Goats, Farini’s Friendly Zulus, Herr Blitz — Plate Spinning Extraordinary or Monsieur Nathan, Marvellous Chair Manipulator, became the staple diet. You get the feeling that those who supported the edifying idea of a erecting such a place where little Herbert would have his Imperial aspirations enlarged by gazing at the behemoths of the deep and the wonders of the wide Sargasso sea, were more than a little miffed at the sort of clientele that the Aquarium’s theatrical shows were attracting. Just one step up from the dissolute ‘penny gaffs’, the Aquarium became a byword as a pick up place.

By the late eighties the building was on the market to the relief of the local upper classes. One alternative proposal was to site the National Gallery there “…then would the great Abbey be no longer disturbed by the performances of music-hall entertainments such as now take place under the very shadows of its sacred towers.” That plan did not come to much. In the end — and its end was in 1903 — came an even greater comfort to the Abbey curia — well, maybe. The Methodists moved in. The dissenters built their Central Hall from the proceeds of a national fundraising known as the ‘million guinea collection.’

Always designed with the dual roles of worship and conferences in mind, it played host to Ghandi, Churchill and Dr King (no, not together), the first meeting of the United Nations and the first performance of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat. The Methodists in their turn vacated in 2000, making it nowadays yet another gathering place for middle management in shiny suits to consume warm white wine redolent of battery acid and shoot what might laughingly be described as the breeze.

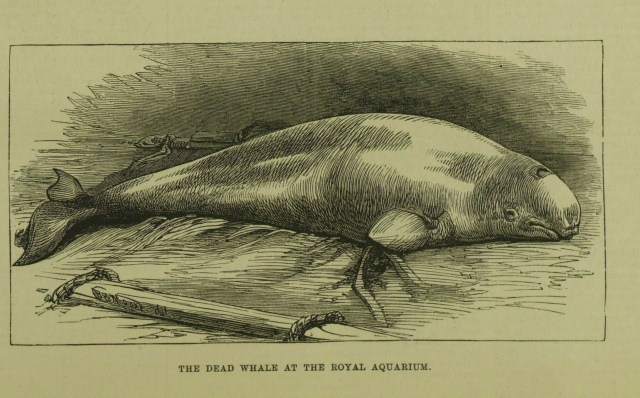

Bring back the whale…