The Civil War was a memory. In the first five years after the war’s end many of carpetbaggers and scalawags had been found out by resentful losers reposed in the Southern States and so some of those northern infiltrators and Southern turncoats, high on quick riches and low on moral self worth redirected their attention to Europe.

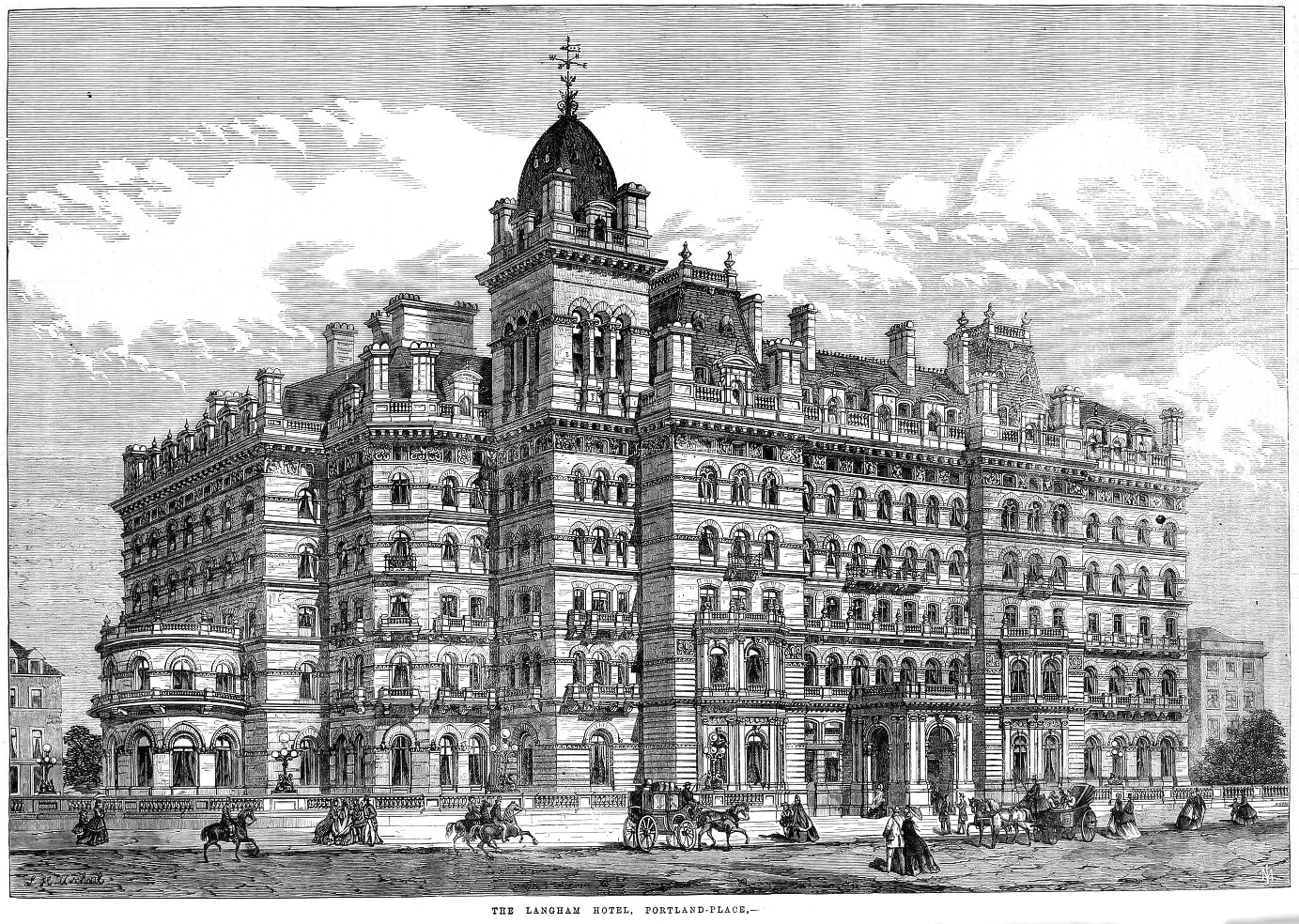

A posse of shady Americans wishing to hoodwink the British with the title deeds to exotically distant worn-out mines or cattle ranches replete with lush grass and sweet natured neighbours arrived en masse in London to set up base. For their home away from home they chose the Langham Hotel.

These Americans had to stick together as many of them were not widely welcome in polite society. The Wall Street Journal attacked this guild of speculators in 1871 and The Times the following year called them “mere western adventurers with nothing to spare of either capital or character, who could not find a respectable banker in New York to co-operate with them.”

When it opened the summer the war ended in 1865, the Langham Hotel had much to offer American expatriates — and not just the con tricksters. From the day it opened, it was run on ‘American lines’. That meant its suites had their own private bathrooms and even for the less opulent, just taking a room, there were more shared bathrooms than was the norm in London. The hotel had its own artesian well to supply its own in-house laundry and more importantly to those that knew London’s reputation (‘don’t drink the water or eat a salad’) to provide pure drinking water from which the risk of disease had been removed. And with 38,000 gallons of water pumped up to tanks in the roof, fire was less of a risk than with some older London hotels. It even boasted lifts for people and for their luggage – six people at a time could travel in the hotel’s guest elevator or ‘rising room’ to use a name destined not to catch on.

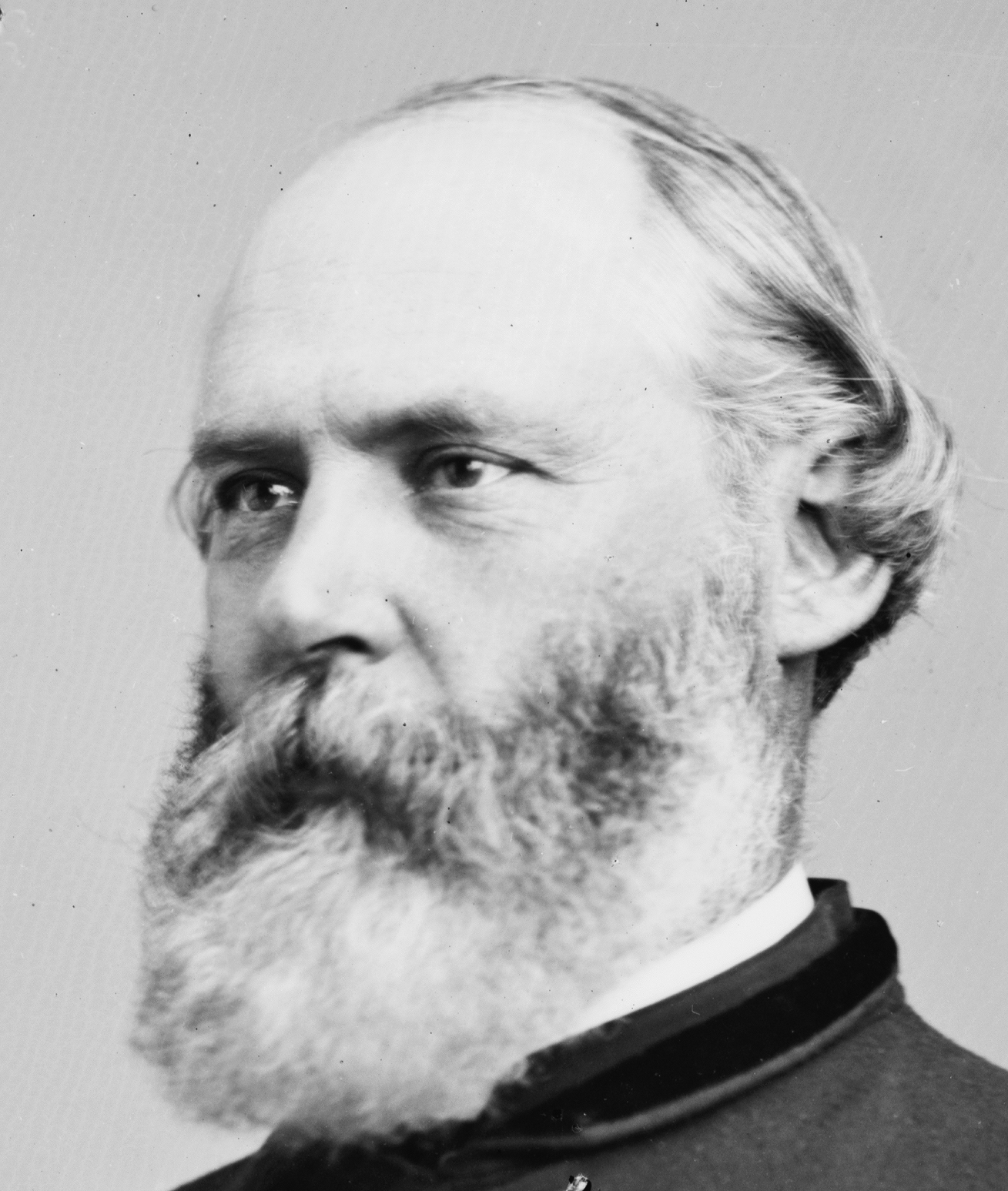

Above all in the damp and dreary winter climate, the American plan meant heat. This point was made by an American traveller so world weary and such a moaner about things foreign that you’d almost take him to be English. He was John Weiss Forney, journalist, editor and minor politician. By his photographs he has something about him that reminds one of the contemplativeness of mid-life John Wayne, and in a way his stance on America’s supremacy among nations reminds one too.

This is Forney writing in his Colonel Forney s Letters from Europe some three years after the Langham opened:-

“I am stopping at the Langham Hotel, at the southern extremity of Portland Place, which is regarded as the healthiest site in London, overlooking the noblest thorough- fares in the metropolis and commanding a view of the broad walk of Regent’s Park, and, on a clear day, of the beautiful heights of Hampstead and Highgate. As this establishment is now in charge of an American, Colonel James M. Sanderson (formerly of Philadelphia), and is partially conducted upon American principles, being in this respect an experiment in the British metropolis, a few words in regard to it may not be uninteresting.

The difference between the English and American hotels is, in my opinion, largely in favor of the latter, and the success which promises to crown Colonel Sanderson’s effort strengthens this conviction. While there are undoubtedly many ideas which the American hotel-keepers might get from their English associates, nothing is clearer than that the system so successful in our country will, when fairly tried, supersede many of the English habitudes. Colonel Sanderson has adopted a plan which unites the best points of the three systems, English, French, and American the comfort of the first, the elegance of the second, and the discipline and organization of the third. You cannot enter an English hotel without being instantly chilled.

Even the Langham, with its American guests and kindly English faces, is cold in comparison to such establishments as the Continental in Philadelphia; the Brevoort in New York; and Barnum’s, in Baltimore. The English people are undoubtedly more home-like than the French, and therefore more like our own; but their hotels are, to my sensibilities, exceedingly repulsive. Of course, much of this results from the fact that every thing is strange to me; but no Englishman that I have met, especially of those who are enjoying the comforts of the Langham, refuses to admit that in many respects our hotels are superior.”

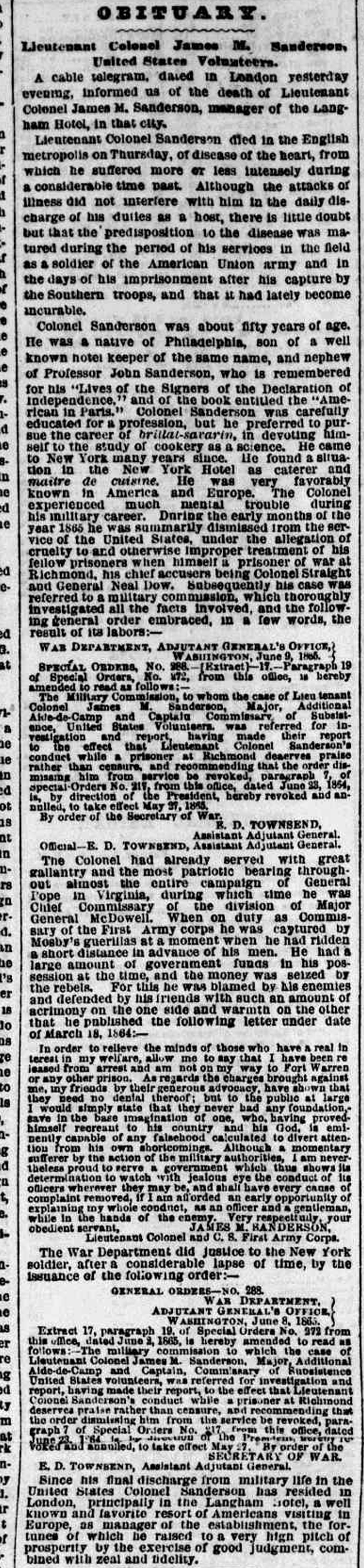

So who was this American, Colonel James Monroe Sanderson, that Ferney praises?

How he got the Langham job harked back to 1860 when the callow young Prince of Wales was sent to North America to polish his diplomatic skills, pat the locals on the head and sow a wild oat or three. Much to the chagrin of the Canadians, the American Sanderson was seconded to organise the catering on the royal progress and occasionally to act as chef. Queen Victoria’s son and heir remembered Sanderson and so when the Langham went through a bad patch, HRH put in the word with the chairman – and you did not turn away a recommendation from the next king of England.

Sanderson’s was a back-story that reminds us all that there was once adversity out there the kind of which we no longer suffer.

Sanderson was born in 1817 and grew up in Philadelphia. You could say that hospitality was in the blood as his father was a hotelkeeper too. Together they ran the best hotel in Philadelphia, The Merchant’s Hotel on 4th St and young Sanderson added a resort hotel, the Brandywine Springs near Wilmington to the list in 1839.

By the mid forties Messrs Sandersons had a chain of hotels and franchises. They were a notable success. Then came the war and the need to provide huge numbers of men with food and the means to cook it. Sanderson was commissioned to the vital role of commissary management, some said without taking any pay. By 1863 he had been promoted to lieutenant colonel.

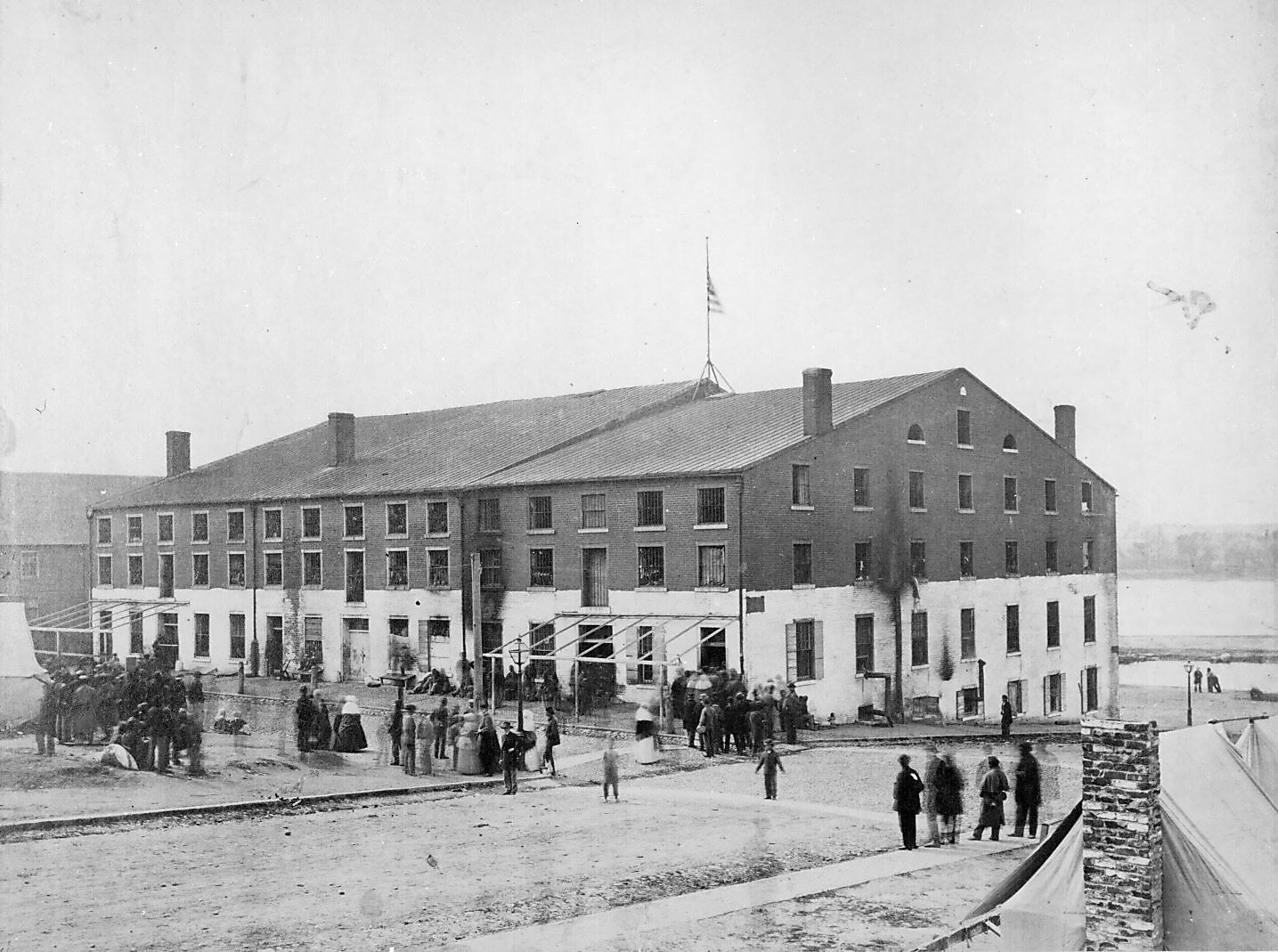

He wasn’t a stay-at-home soldier though and while reconnoitring a stream crossing he was caught and incarcerated in a warehouse turned into the notorious Libby prison. Bars instead of glass at the window and gross overcrowding meant that conditions were primitive and disease spread rapidly. Sanderson, whose role had previously been to give practical advice to the average soldier on how to feed himself took similar charge inside Libby.

Before he arrived the prison had already divided into factions. Very soon Sanderson fell out with a man who had taken over much of the top floor accommodation for himself and his cronies. Lt Colonel Abel Streight and Sanderson became the sort of enemies that only close proximity in a school or prison can sustain.

When Streight, Sanderson and 107 other officers escaped the jail through a tunnel on the night of February 9 1864, Sanderson was shocked to find that when he got back to the Union side he was arrested on the say-so of Streight. Sanderson’s alleged crimes were many. He kept food from the others, he even stole the egg nog destined for the hospital and most importantly he provided information to the guards.

When a trial failed, Sanderson was ignominiously dismissed the service by June of that year. After a fight he and his friends got him re-admitted to the army by August and then honourably mustered out.

Enough must have been enough for Sanderson among the East Coast establishment so that when he got the call from the Langham he packed his trunk and said farewell to fractious New York and his enemies.

But on Thursday morning of November 16 1871, just after he had given staff instructions about the wedding breakfast that was take place in the coffee room later, Sanderson felt faint and collapsed on this way from the cellar to his office. He was taken to the boardroom where, though he was conscious for a half hour, he died. Within the week his body was heading for Liverpool and a ship to take him home.

Nevertheless, he got a good write up:-

1 comment

Comments are closed.