Bull running in Lincolnshire? Why haven’t I heard of it?

Thankfully because it was banned long, long ago.

You probably don’t want to know what happened to each year’s Stamford bull on the feast of St Brice’s Day, but it wasn’t a happy day for el toro on November 13. Rules demanded that while the thousands of men, women and children of all social classes who turned out on St Brice’s Day could bring their own cudgels to hit the bull, it stipulated these must not be edged with iron. That would spoil the fun after all. Nevertheless organisers delighted in making the bull more frightened and thus angrier by such tricks as cutting off its tail or setting off a trail of gunpowder along its back. A good day’s sport was if the poor trapped animal could be goaded over the parapet of the bridge and land up in the shallow River Welland. If they could make it happen before midday then they would get another bull for the afternoon’s goading.Strange folk, our ancestors.

Which brings us neatly to 1788. As the local paper declaimed: “Friends of humanity will with pleasure hear that the brutish custom of running a bull all day in this place has this year been prevented by the attentions of our worthy magistrates”.

A troop of militia, a few arrests and the paper felt it could proclaim “…we trust there is now an end to a custom which has long disgraced the town of Stamford”.

But pagan customs never die as easily as that. It had not actually gone the way the paper said it had. What the paper did not say was that first of all the mayor had declared involvement with the running of the bull was punishable by death (though where he got the authority to rewrite the criminal code is not clear). The mayor roped in a local worthy, the Earl of Exeter to add weight to his argument. Like all of his kind, Exeter followed a perverse English custom by living nowhere near the place he was earl of, and therefore lived in Stamford, not Exeter.

Both the earl and the mayor were jostled and shouted at on St Brice’s day by the rebel rabble intent on killing a bull. Being jostled was definitely not the done thing for a minor aristo and town worthy. So they planned their revenge for the following year.

In 1789 both sides in the bullfight were in a ‘bring it on…’ mood. When St Brice’s day rolled around the mayor had his plan. With his troop of dragoons he met the bull and its keeper, one Anne Blades, aka ‘the bull woman’ and described as “a virago dressed in blue rags”. She was actually in a blue farmer’s smock frock and carried a blue cudgel, along with a collecting box for donations to pay for bull and her drinking habits. Behind her were the usual bull running peloton, or the bullards as they styled themselves They were infected that year with the republicanism of the French who had liberated the Bastille that summer, and were going to better their betters.

Things went wrong for the mayor when he commanded his dragoons to arrest everyone. Sadly, the mayor had misjudged his dragoons. The dragoon commander said the bullards were merely walking peaceably along the highway and he would take no such action. The mayor flew into a hissy fit and dismissed the soldiers — who promptly switched sides and joined the bullards — and so the bull inevitably died.

So popular was this sanguinary circus after this episode that the town voted to hold a further bull run each year on the first Monday after Christmas Day. And so it went on for nearly another half century.

Earlier than perhaps you might imagine, 19th century legislators had begun to be concerned that some poor treatment of certain animals was below Christian standards. The year 1822 saw the Cruel Treatment of Cattle Act introduced. Its sponsor was “Humanity Dick”, the Irish animal rights activist Richard Martin MP.

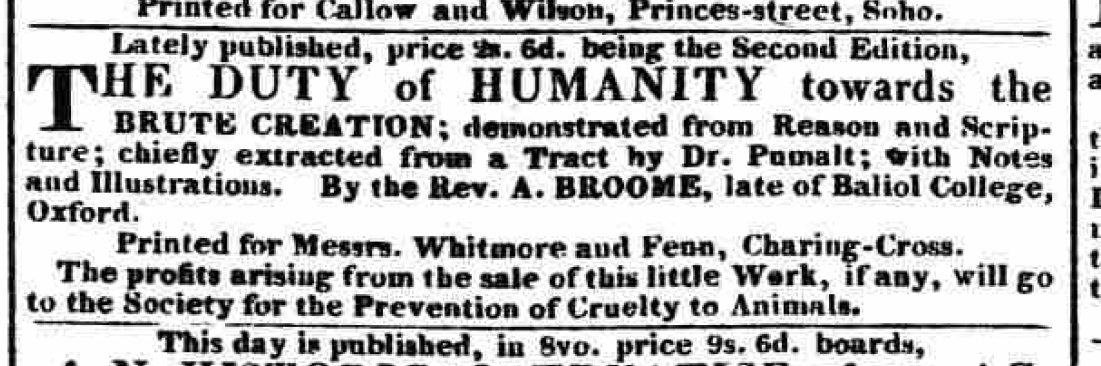

Probably best not to argue the toss with Humanity Dick though, as his other nickname for this protagonist in more than 100 duels was “Hair-trigger Dick”. Richard Martin, along with anti-slavery champion William Wilberforce and a drunken priest named the Reverend Arthur Broome were in at the foundation of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1824.

Later, after Queen Victoria took an interest and gave it a Royal accreditation, re-named the RSPCA

Later, after Queen Victoria took an interest and gave it a Royal accreditation, re-named the RSPCA

Though Martin’s Act mentioned all kinds of cows and oxen, it omitted bulls. Why, you may ask? Politics was the answer. Stamford was not unique in goading a bull to its death.  Bull baiting, like cock fighting and dog fights, were the sports (if you can call them that) of the potentially riotous poor. For the establishment which had as its aim social engineering, or to put it in 19th century language “eradicating brutality from the minds of the people”, the danger of depriving the Untermenschen of their pastimes was twofold. The more urgent would be local civil disorder, but an elephant in the room was actually a fox. Reformers and hand wringers were beginning to pose the uncomfortable question why was it less cruel for the rich to pursue a fox to death than the poor its bull?

Bull baiting, like cock fighting and dog fights, were the sports (if you can call them that) of the potentially riotous poor. For the establishment which had as its aim social engineering, or to put it in 19th century language “eradicating brutality from the minds of the people”, the danger of depriving the Untermenschen of their pastimes was twofold. The more urgent would be local civil disorder, but an elephant in the room was actually a fox. Reformers and hand wringers were beginning to pose the uncomfortable question why was it less cruel for the rich to pursue a fox to death than the poor its bull?

So the bull running continued sporadically throughout the 1820s and 1830s. It is some irony that it was only when national government stepped in to issue edicts forbidding it that the gradually disinterested folk of Stamford felt that they were being pushed around and revived their day of blood in the mud.

On a number of years bulls were smuggled into town, while the inevitable dragoons, locally sworn constables and a troop of the recently formed Metropolitan police from London did their best to control the thousands of bullards who came from miles around for drink, mayhem and a chance of a roast beef supper.

What finally persuaded the burghers of Stamford to take bull off the menu was simple. Ratepayers — that is to say the middle classes — were hit with the policing bills over and over again until they saw some sense.