Moving the entire Crystal Palace from Hyde Park nine hilly miles to that vale in Sydenham after the Great Exhibition closed in 1851 was an audacious piece of Victorian chutzpah, but it was by no means unique in that age of civil engineering audaciousness now long passed from the Western psyche.

Think first about how you would do it, to dismantle it — by hand. They took down an entire building some 1500 feet long and three or four storeys high. Men had to work far above the ground without any of today’s safety equipment, in order to unbolt each and every wrought and cast iron girder arch. That was after they stripped off all the acres of glazing. The girders then had to be lowered to the ground by steam powered cranes or the muscle of the labouring men. Then they had to be labelled, put onto wagons and taken through the streets — and these were big pieces of ironwork that probably needed a six horse team to pull them. They must have stopped traffic as they negotiated their way through narrow streets.

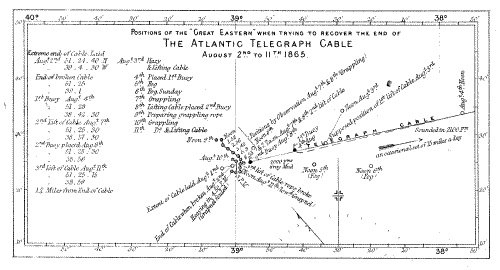

But that was by no means an achievement in the top ten of what the Victorians did. As early as in 1843 English engineers had tunnelled under the Thames. In 1881 they started digging a tunnel under the English Channel, that only security fears and private money problems kept the from finishing. The Suez Canal was completed in 1869 and the Panama Canal was proposed before that, though not begun until 1881. In the late 1850s – and that was 30 years before half of the bridges across the Thames were built, people believed in their own invincible abilities enough that they sank a telegraph wire to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean to connect the 3,000 miles between the continents. When it failed — and then its successor cable broke and sank in mid ocean in 1865 — what did the Victorians do? They simply sent out a ship and, with a grappling hook, fished for the cable until they found it. That was the indomitable spirit of the age. Where did it go?