The Rock Springs Massacre of Chinese workers was recalled at a website I follow and respect Nothing Gilded, Nothing Gained http://middlemaybooks.com/2014/06/20/chinese-immigrants/ It led me to thinking; firstly that there must be a switch in men (though women, especially young women in groups with alcohol aboard seem to be learning fast) that when flicked gives us Year Zero, My Lai, Oradour, (see my previous post) and the ovens of Belsen, Wounded Knee,The Cathars and all the rest.

But is it racism as such? Is it any kind of -ism at all? Isn’t it something else? The Norse had a word, beserk and Malay another, amok which seem to capture this brooding building to frenzy. It may be about otherness of strangers, but might it be about something other than race?

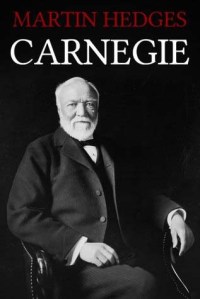

Then I also recalled what I wrote in a biography of Andrew Carnegie last year about the undeniable climate of racism that American unions fomented for 50 and more years from the 1870s.

“Capitalism was adjusting to the uncomfortably plain fact that, try as owners might, nothing would prevent workers organising to use collective bargaining. There was no going back to the days when ‘combinations’ of workers were illegal gatherings.

Industrial workers from steel plants to garment factories and even cigar rollers were feeling for their rights through unions. There was no right or wrong side in this urban warfare. Employers resorted to a form of state-sanctioned violence to quell what would now be seen as relevant grievances.

State and Federal authorities were forced to act, often not as supporters of capitalism as unions portrayed them, but as keepers of the peace, for often strikers used disputes as an excuse for drunken mayhem and riot.

As an example, when at the end of the Civil War and falling iron ore prices, the miners and dock workers of Marquette, Michigan downed tools and stormed the town, a navy vessel on Lake Superior unshipped its guns. The captain issued an ultimatum. He made no excuses for his use of force, saying of the riotous miners: “They were told that twenty-four hours, and no more, would be allowed them, and if by that time they were not at work, and the ore loaded in the idle cars, that encampment would be stormed by shot and shell, and no questions would be asked or answered. There must be no more rioting, no more idleness, and no more threats.”

Pittsburgh had a history of strikes turning ugly. Though the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 was widespread across the East Coast, it was at its most violent in Pittsburgh. During the strike, the Pennsylvania Railroad (which had continued to pay shareholder dividends since the crash of 1873 while cutting workers’ wages by ten per cent, not just once but on each of two occasions), suffered 1200 freight cars and 105 locomotives destroyed and $3 million in lost business, while the National Guard killed 20 rioters. The city’s passenger station was burnt to the ground. Order was only restored when Federal troops systematically crisscrossed the country’s troubled cities putting down the workers’ rebellion.

Strikes and lockouts, union intimidation of those that wanted to work, scabs and Pinkertons were the tools of labour and capital. The Pinkerton Detective Agency came to prominence in the Civil War when Glaswegian émigré Alan Pinkerton guarded President Lincoln from a rumoured assassination attempt in Baltimore before his inauguration.

Pinkerton’s business grew to be a private security force for hire. An employer could rent by the day armed and uniformed men to protect his factory and those workers braving picket lines. The Pinkerton National Detective Agency offered other services, including undercover agents used to penetrate the unions to discover the ringleaders and their strike plans

Trades Unions were run on a secretive Masonic model. They gave themselves grandiose titles like Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, Sons of Vulcan, or Brotherhood of Engineers. They struggled to represent their members, but those members were almost always in craft trades. Unions did not represent the vast pool of the labourers who did most of the work and most unions drew the line at other races than white.

Unions struggled for a number of reasons. Every day new immigrants from Finland in the north to Sicily in the south would detrain in the industrial capitals of America seeking work. And the first job an immigrant found was often an underpaid task that others did not wish to do. Bosses used this conveyor of humanity – replacing Irish with Germans and Germans with ‘Hungarians’ (often shortened to Huns and an insult aimed at any nationality east of Prussia) as each group wised up to the advantages of pay bargaining.

Industrial progress was the enemy of the elitist and conservative craft unions. Puddling iron – kneading a 200lb red hot paste of iron around a seven foot square open furnace with long iron rods for half a working day to reduce its carbon content was not only hard and very dangerous; it was a dark art that required a long apprenticeship. New machinery in steel making and in every other industry was deskilling tasks and cutting numbers needed. Deskilling meant that employers could quickly hire in strike-breakers, often from that pool of immigrant labour and train them in weeks to do the jobs of the strikers. As there was nothing in it for the day labourer even if a union won more pay for its members, there was usually little support from among the poorest and hardest suffering for the relatively better paid union men.

Unions had demanded and got some worker concessions. Mandatory breaks during the long 12-hour shift and a certain degree of grievance rights too, but unions had claimed much leeway and it turned into abuse. Too many bosses had conceded that the union could act as parallel management, with the local union bosses choosing for themselves who to hire and who to fire. Unions favoured their own and so the number of union men increased exponentially in a unionised plant. This restrictive practice prompted corruption that became impossible to stamp out.

Both sides were willing to use violence routinely. Bosses brought in the Pinkerton private army when they could not rely on their local sheriff’s deputies or a regiment of infantry to break strikes. Bosses had little to lose, insulated as they were by their wealth to withstand a long dispute. Workers, whose families faced grinding hunger and cold during a winter strike had the stark choice – fight or capitulate.

It was never as simple as noble working man versus evil capitalist barons. Populism in unions engrained corruption. A particular trade or department in a factory was often monopolised by one ethnic group — Irish, Welsh or Germans — and the union blocked hirings that did not fit their closed shop and blatantly restrictive working practices. Racism was openly practised by unions, ostensibly on the grounds that new immigrants undercut wages, but on occasion it was plainly just on account of race. In September 1885 at least 50 Chinese coal miners and most probably many more, part of a long-established Chinese community in Rock Springs, Wyoming, were murdered in riots that were inspired by the Knights of Labor. The union local’s excuse was that the Chinese had at one time been strike breakers. The union’s national boss made no apologies for the massacre: “”It is not necessary for me to speak of the numerous reasons given for the opposition to this particular race – their habits, religion, customs and practices…”

Among the vast pool of immigrants from Europe had come a substantial number of rabid socialists and anarchists, notably from the German principalities. Their intent was to create a new Zion using the dynamite bomb. They were attracted to labour disputes as and when they happened. They hijacked speechmaking and picketing into the violent war against capital.

Chicago’s Haymarket riot on May 4th 1886 was synthesis of all the issues besetting labour relations. The dispute was for an eight hour day at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company. That prompted a strike in Spring. The response from management was to lock out the strikers and bring in non-union strike-breakers. On the previous day a protest outside the plant had seen two workers killed. The next evening a peaceful protest meeting in central Chicago was just breaking up without incident when a police squad marched up to order the speakers and audience to disperse. A bomb was thrown at the police, killing one. The police drew their revolvers, shooting indiscriminately and killing many, including six more of their own. In a palpably unfair trial four anarchists were summarily hanged. As a result of the outpourings of handwringing newspaper coverage over the riots, the reputation of unions – especially the Knights of Labor — was tarnished.

There was inevitability about the many pitched battles between workers and management at this time – classic doctrines of property rights versus what have now become labelled human rights were being fought over. For the working poor these were not the milksop rights of the 21st century they were seeking, but clawing back decisions of life and death that were eradicated when squirearchal noblesse oblige had been overtaken by return on capital. The battle of Homestead represented victory for Frick and Carnegie and was certainly a defeat for trade unions, especially for the union most associated with representation in Pittsburgh steel, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers.

Here is a perspective from just 30 years afterwards:-

“This famous strike attracted world-wide attention, and well it might, for it marked a turning point in the industrial history of America. It began on June 23, 1892, and lasted until November 20 of the same year. Characterized by extreme bitterness and violence, it resulted in complete defeat for the men, not only in Homestead, but also in several other big mills in Pittsburgh and adjoining towns where the steel workers had struck in support of their besieged brothers in Homestead. This unsuccessful strike eliminated organized labour from the mills of the big Carnegie Company. It also dealt the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers a blow from which it has not yet recovered. It ended the period of trade-union expansion in the steel industry and began an era of unrestricted labor control by the employers. At Homestead Carnegie and Frick stuck a knife deep into the vitals of the young democracy of the steel workers.”

The Great Steel Strike and its Lessons; William Foster; Huebsch 1920

The robber baron image popularized in the 1920’s fails to take into account the humanity of upper management and the great leaders of corporations who made up the rules as they went having nothing to compare their colossal corporations to in the past. It’s easier to point a finger and call certain men evil (and Jay Gould doesn’t seem quite nice) but we all tend to rationalize our stupidity and crazy urges–rich men are no different. Poor men are no better.

I’m recalling the times that unions fought to keep the rails from making changes that would have made certain jobs less dangerous for fear the job would become de-skilled. We’re all crazy in the end.