There is a time when ‘principles’ become not a good thing but an obsession. Like jealousy or revenge, stubborn adherence to ‘principles’ taken to a point where they are self-harming can erode the mind.

This old man does not sound deranged but as he calmly gives his testimony, he does sound profoundly broken and angry. Has he let ‘principles’ overtake his right mind..? you can decide.

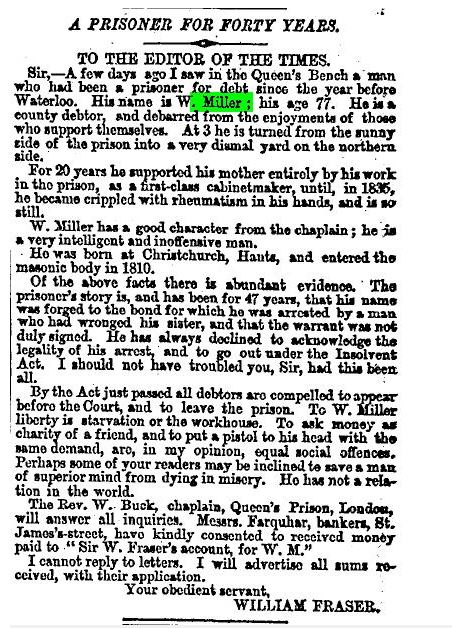

It is 1861 when the British papers carry the report of a debtor up before the authorities to explain why he should be discharged from his debt. This happened all the time though. A businessman or a tradesman who could not pay his bills went through these hoops every day.

But in earlier times than 1861 a debtor was put in jail to concentrate his mind about paying his creditors. Dickens’ dad was an example. But in the enlightened 1860s the debtor was simply made to account for himself financially and if it seemed he was an innocent who had run out of money rather than a fraudster he was discharged from bankruptcy after a couple of years. As part of the tidying up process debtors were found still in jail and were being set free.

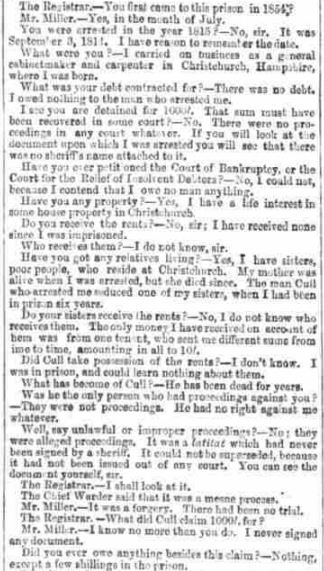

This man before the court was a victim of those ‘earlier times’. He should have been angry and who could blame him? The arthritic old man, William Miller by name is speaking under oath to the registrar of the Queen’s Bench Prison, an humane man who is only trying to clear up now what authorities should have done five long decades before – release William Miller from a debtor’s prison as seemingly he had never been a debtor in the first place.

It is a murky story and one has to suspend disbelief or the truth of everything Miller testifies, but from his side the facts are these. In 1814, yes that’s right 1814, Miller was a carpenter and cabinet maker in the sleepy Hampshire town of Christchurch. Miller still can recall the day — Saturday September 3rd that his Kafka-esque nightmare began..

He says that a man named Cull accused him of owing the absolutely eye-wateringly huge sum in those days of £1,000. How a simple carpenter could run up what was the equivalent of millions nowadays is never questioned. Cull has him arrested and thrown into debtors’ prison, where he still languishes in 1861 (though since 1854 he had been moved from Winchester prison to London).

Miller forcefully and clearly states that the paperwork that put him there in the first place was unofficial, unauthorised, illegal and possibly forged. He adds that he owned property in the town that would have provided rents to satisfy at least some of the debt but the money went missing. Miller claims that there is further back story attached to his jailing in that, according to Miller, the man Cull had seduced one of his sisters. As this possibly occurred before Miller was incarcerated, that might present circumstantial evidence of malign motive on Cull’s part.

The kindly registrar named Winslow told the sickly 77-year-old man that he would release him that day if only he would declare himself bankrupt, but the old man stuck by his principle that no man should acknowledge that he was a debtor when he plainly was not. The unspoken fact was that fifty years had institutionalised Miller beyond redemption. He was simply scared of the fate awaiting him outside prison.

Independent evidence is scant today to corroborate Miller’s story . If absence of evidence is ever evidence of absence this might be the case. It was the law that every bankrupt Tom, Dick or Harry across England got his name published in the official London Gazette as part of the punishment. And while there were dozens of bankrupt millers by trade that year there were fewer Millers by name and none named William nor any within 100 miles of Christchurch in 1814.

There was a family named Cull residing in Christchurch at that time. It was in a position of some power in town, with one member acting as the town’s auctioneer. That man had a son who was the right age to be a seducer during Napoleonic times but that isn’t proof.

William and Miller is such a common coupling of names that most villages would have record of one, so that haystack may hide a needle, who knows? However, there is a record of an 84-year old named William Miller dying in Christchurch in 1867, so that may have been our man, as their respective ages almost match. For he was released — probably as much against his wishes as his original incarceration was. One can only hope that those six years he had left were better than the rest of his adult life, stolen from him.