In Victorian London most of the poor lived in what would be called slum housing. During the 18th century many ramshackle ‘courts’ had been built as a result of speculative infilling behind street frontages. However, the reputation of one court stands out. For at least 40 years, from the 1830s, there was an enclave in The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea then as now one of London’s richest boroughs that was the very worst of insanitary, animalistic, vice-prone and violent ghettoes that the Victorian age allowed.

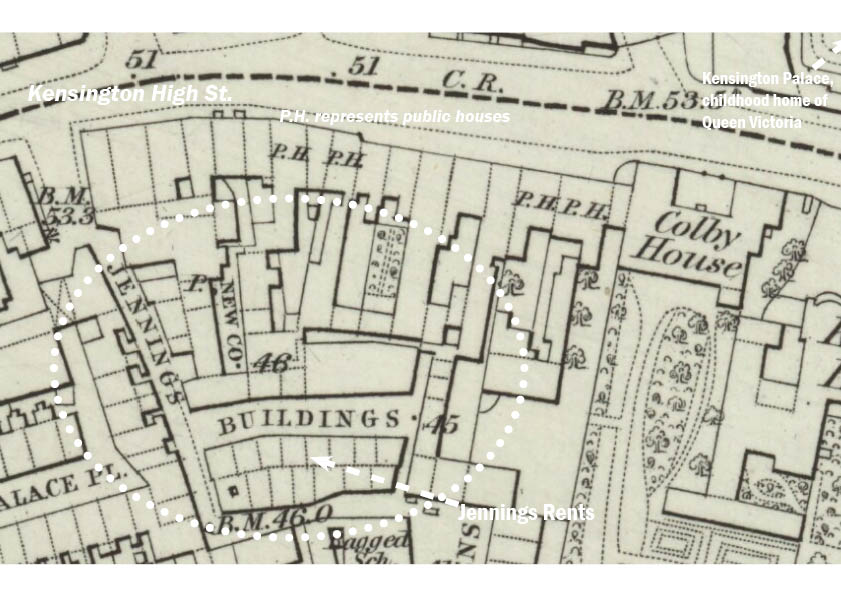

The most awful slums of Seven Dials in Covent Garden were said to be cleaner than this rookery of poverty situated just east of Kensington Square. Its very name — Jennings Buildings or Jennings Rents — was held up as an example of the fearful consequences of overcrowded slum living. When a section of Parsons Green (now and expensive haven of the banking, media and legal young haute monde) was thought to be slipping into bad behaviour, the area was said by the locals to be becoming “another Jennings Buildings”.

From as early as 1835, the 80 or so decaying, mostly wooden, houses down this alley and spreading across five courtyards were said to be home to a ‘colony’ numbering between 1000 and 1500. The very poor, almost exclusively Irish, crowded into dirty lodging houses and shared rooms in firetrap tenements.

To a 21st century sensibility it is hard to believe the depths of depravity discovered by the contemporary eye-witnesses, who observed: “dirty houses, with unglazed windows, dunghills at the doors, squalid and ragged people about them, and in the centre of a small, very small square, an open cesspool, redolent of extremely noxious gases. In fact, every street in this pestiferous neighbourhood assures the passenger that he is exposed to the inhaling of fatal disease with the stinking air which it contains.”

By the late 1840s the ‘Irish malignant fever’, associated with the so-called ‘potato famine’ in the old country had travelled back with the immigrants to the lice ridden slums of Jennings Rents. Some of the sick were carted off to the fever hospital at King’s Cross — though many just remained, or more often died, where they lived. The ‘necessary accommodations’ (as the Spectator coyly styled the few privies on the site) draining as they did into a semi-open sewer, were in such a parlous state that the malignant fever was replaced in 1849 by Asiatic cholera. That such a plague should occur in proximity to the Queen’s birthplace was a stain on the reputation of the borough that travelled far and wide.

It is a danger of historians to fall for the easy evidence gleaned from the police blotter. However, if reported incidents of what drew Jennings Buildings to the attention of the police over and over again, then you might conclude the worst of this pocket of impoverished humanity. Some occupants were doubtless honest families whose men worked as labourers or navvies and whose women as washerwomen for the neighbouring rich. Some others were working the streets as professional beggars or plied their wares as prostitutes. A lot were career criminals.

Mostly they fought. They fought after they drank. Men fought men. Men knocked down women, often their wives or their daughters. Women knifed and tore the hair out of other women. Men stole after they drank, always claiming insensibility as their excuse. Boys fathered children by girls who otherwise earned money from sex with the soldiers at the barracks around the corner.

Of the six pubs within yards of the slum, the Marquis of Granby at number 17 Kensington High St and the Coach and Horses at number 35 were favoured. Perhaps they were the only hostelries that had not barred the occupants of Jennings. The publicans lived a schizophrenic existence. They relied on the trade of these voracious consumers of alcohol, but were beset with customer fights, assaults on the staff and almost constant and audacious thefts — a pewter quart pot one week, clothes from the upstairs maids’ quarters another. The Marquis was often used as the back way into and out of the Jennings alleys when the police were in hot pursuit.

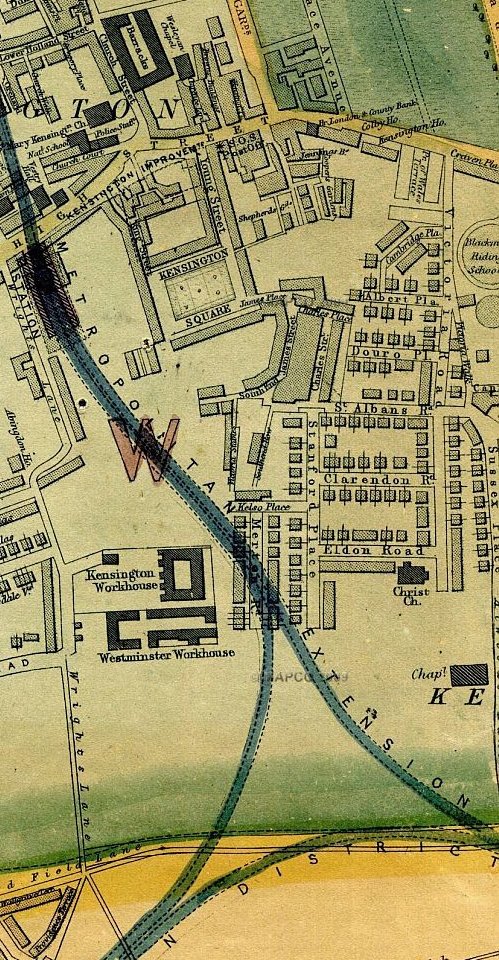

Up the High Street, the London and County Bank, whose customers were the well-to-do residents of the old court borough, was never really secure because of the building’s proximity to Jennings. While the bank was housed in a building whose street frontage faced the carriage entrance to Queen Victoria’s childhood home of Kensington Palace, it was not safe from attack. . A 14 foot high back wall to defend itself from the denizens of Jennings Buildings just beyond the brickwork did not stop chancers clambering over to see what they could steal.

The tops of the Jennings buildings were used as lookout and safe haven the authorities dared not reach. Kids routinely threw stones and roof tiles, coal or bricks at policemen — and remember, this was an era when even the hardened criminal was usually in awe of a uniformed constable.

The owners of the corner shop named names simply to stop this dangerous rain of missiles on their customers. Bad mistake… Police had to wade into a crowd of said to be more than 200 people trying to beat the shopkeeper and his wife to death for breaking the unwritten rule on snitching.

From the start residents of Jennings Buildings began to assert themselves outside their ghetto. Sporadically they spewed forth in numbers to terrorise their affluent neighbours. On one St Brigid’s Eve in the 1830s (St Brigid’s Eve was a Christianised version of a Celtic festival celebrated in Ireland to mark the start of Spring), they scandalised the local shopkeepers by marching their pagan corn dolly effigy up the High St and thrusting her in through shop doorways, sending refined customers for the smelling salts. Police chose not to confront the mob, but arrested the dummy and locked her in a cell until a woman turned up asking to collect her sister’s dress adorning the Celtic goddess.

In the hot summer of 1841 there was a weekend-long stand-off with the law that saw police calling in reinforcements while Irish from other parts of London journeyed to Kensington just to see who they could fight.

In 1845 the summertime tradition of a riot was repeated as hundreds of drunken men and women paraded up the High Street throwing stones, breaking windows and generally intimidating the genteel environs of the borough.

For at least a decade, there were mumblings about buying up the land and demolishing this stigma to Kensington’s good name, though the cash was never forthcoming.

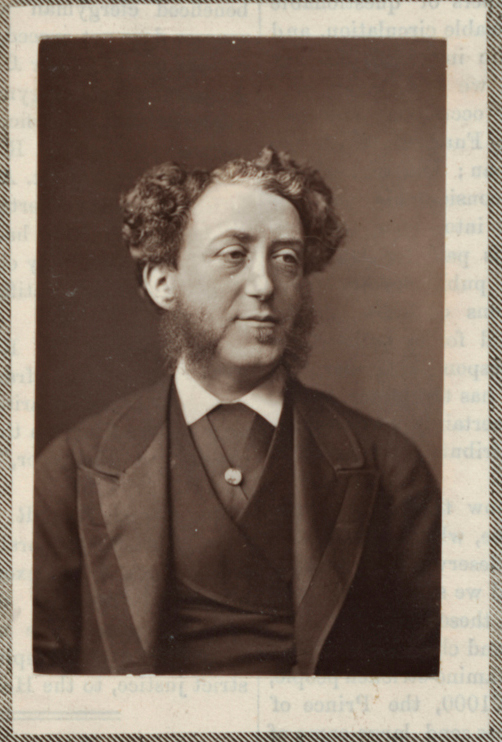

In April 1873 the municipal fathers, shopkeepers and residents alike breathed an audible sigh of relief when it was abruptly announced that various parcels of land comprising the site had all been bought secretly by London millionaire financier, Albert Grant. The news was even better — the denizens of Jennings Buildings would be driven out, after which he would build himself an architect-designed million pound mansion in its own grounds in the French style.

He may have been acknowledged as the sharpest, toughest businessman in the land, Baron Albert Grant was not so stony-hearted when it came to the poor. Though he had no need to recompense the tenants as he had bought the freeholds, he paid them the very substantial sum of two pounds a room to quit. He even allowed the occupants to take away building materials. He either rented or had built some ‘model’ alternative accommodation in Notting Hill, though it did not find favour with many Jenningsites. While that may have been the carrot to persuade them to leave, there was a stick. Grant was also said to have employed a little bit of subterfuge, by organising a day out (doubtless with booze) for the Jenningsites. They jumped at the chance, but returned to find that workmen had pulled the roofs off their homes in their absence.

Grant explained: “When I found it absolutely indispensable that the dens of vice and infamy which the parish authorities of Kensington had been trying for many years in vain to break up and remove, known as Jennings buildings Rookery, should be pulled down, I carefully considered the fact that the occupants had a right to a ‘local habitation,’ though, being only weekly tenants, they had no ‘legal claim’ on me for one. What however, I did was to pay each tenant a voluntary money indemnity, for which they were very grateful and, in addition, gave them an option to remove to model lodging houses at Notting-hill, the whole block of which I had expressly taken for the accommodation of the poor people, whom, for their own sakes as well as my plans, it was necessary to remove from the horrid dens they inhabited, to their own danger as well as that of the whole neighbourhood. Some of these gratefully accepted the accommodation found for them, but the bulk of them preferred going to other districts in Chelsea, Battersea, Kensington, &c, where they found rooms free from the necessary restraint of model lodging-house accommodation.”

So the rookery was flattened. Some 650 men toiled for two years to build Grant’s palace. Many feet of the vile ordure that penetrated the topsoil was scraped off and The Jennings Rents part of Grant’s many acre garden became a large boating lake full of ornamental fish.

1 comment

Comments are closed.