There are contrary versions of this story. One has a man who thought he could ride on the coat-tails of an illegal scheme, who got caught and rightly, though severely, punished. The other version says that an ambitious but innocent man was cynically cut down by corrupt and overweening authority.

Was it political vindictiveness and a government stitch up? It was in the middle of the Napoleonic War. Successive governments had been waging war against radicalism in France since the Revolution and so it was tough on radicalism at home. Rigged verdicts in political trials were commonplace. When a low-grade scandal came along, the government of Lord Liverpool saw an opportunity to use it to denigrate a Whiggish (what might now be called liberal or left wing) naval hero and MP named Thomas Cochrane. However, Cochrane probably had some part in a particularly lame plot that became known as the Great Stock Exchange Scandal of 1814.

‘Great’ was a misnomer judging by later scandals which would unveil themselves in the century. More a practical joke taken too far than utter criminality, it was a second rate farce which went wrong. It was quickly discovered. Any gains were frozen and subsequently never awarded to the originators of the deception. But it was temporarily the ruin of 39-year old Lord Cochrane.

Admiral (eventually) Thomas Cochrane, the tenth earl of Dundonald, has often been fictionalised. He was the model for Midshipman Easy and Captain Hornblower. His character has been played on-screen by Gregory Peck and Russell Crowe.

Cochrane was a Regency combination of Captain Jack Aubrey from Master and Commander and Top Gun‘s Pete ‘Maverick’ Mitchell. His adept tactical handling of sailing ships in war and his guile in combat were legendary. He even perfected one manoeuvre that was to be later used in the air by Soviet fighter pilots and replicated onscreen in Top Gun. Once, when pursued by three faster ships in storm force winds, he had his crew fix ropes on every sail As the enemies closed at full speed he ordered his men to simultaneously haul the sails up – stopping his ship dead in the water. His opponents shot past and they sailed on for miles before they could turn to pursue him. As night was falling, he he then lowered a lantern in a cask over the ship’s side and dowsed all other lights. The pursuers followed it rather than his blacked out ship.

Why go for him? He was the golden boy of the navy, but had made many enemies by being as good as he was. He was a radical who believed in political guerilla tactics to prove his point. Cochrane previously had the temerity to publicly label his commanding officer, a certain Lord Gambier, a coward. As the man was related to late Prime Minister William Pitt by marriage, that may have been a blunder on Cochrane’s part. Cochrane was a danger to the Establishment and he needed metaphoric assassination if and when the opportunity arose.

The Stock Exchange plot was organised by his wicked uncle, a man called Andrew Cochrane Johnstone, along with the uncle’s stock broker. Cochrane Johnstone was a youngest son whose career in the army came to a halt when he was found to have been using the troops under his command in Dominica as his personal plantation workers. As an MP he was kicked out of a particularly rotten borough for being even more corrupt than other MPs. Fleeing back to the West Indies, he was nearly arrested for bribery and fraud while an agent for the Navy, but escaped once more to England. Next he sold guns to the Spanish, though he took the money and did not provide the weapons. So while uncle Cochrane Johnstone was pretty easily identified as the man who thought up the fraud, you could suppose that Cochrane knew something about it – and to have allowed himself to benefit from it, even if he was not actually an active plotter.

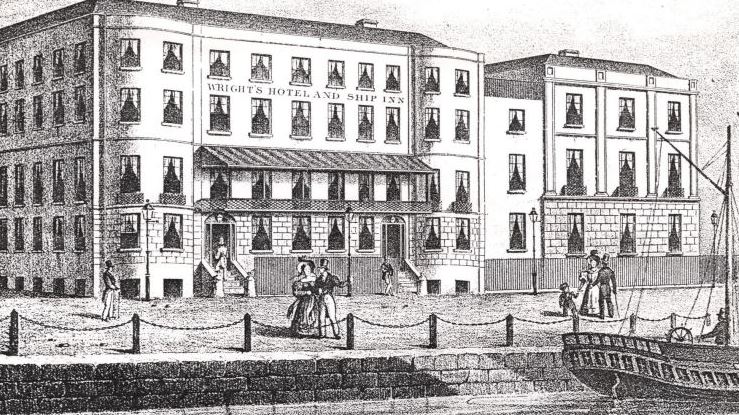

The place to stay in the Channel port of Dover during the Napoleonic war was The Ship Hotel. Right on the quayside by the Custom House Dock, this four storey, flat fronted building was so much more than the equivalent of an airport hotel for departing and wearily returning travellers from France. It was a society hang-out akin to the Dorchester or the Four Seasons. Europe’s travelling royalty, the Duke of Wellington, the poet Byron and Marshal Blucher all stayed there on their way to or from London.

Very late on the evening of February 20th 1814 a less notable man in a travel stained scarlet soldier’s uniform, marched up the dozen or so stone steps and banged on the main door of the hotel. He was fresh off a ship called the Eagle just arrived from Calais (so he said). He had astounding news.

Since the woeful French retreat from Moscow the previous winter, there was an inevitability in 1814 about the allies’ final victory against Napoleon Bonaparte. If it were a boxing match the fight would have been stopped, but like so many wars before and since, it was to be fought on for too long after that unavoidable realisation was obvious to both sides.

He called himself Colonel de Bourg, claiming to be an aide to a British commander who had been leading the British army units liaising with the Eastern Front. His news had the few top hatted gents and uniformed officers still up in the smoking room huzzahing, waking the rest of the guests. The news de Bourg brought was that Napoleon was dead – killed by Cossacks, with his body literally torn apart for souvenirs. The allies were heading for Paris and the peace would imminently be made official.

At one o’clock in the morning of the 21st De Bourg sent for a messenger to travel the nine miles along the coast to the Admiralty semaphore telegraph station at Deal. He wanted them to send the tumultuous news to London, which they dutifully did around 4am in the morning on the 21st. As the story would seem to come through official sources, it would be believed on the Stock Exchange.

De Bourg next rented the fastest mode of transport he could get – a post chaise and four horses – and headed for London, stopping off at towns along the way to re-seed the rumour by handing out gold Napoleon coins as tips in order to demonstrate the heady abandon that would come with the imminent cessation of fighting. In London he abandoned his hired chaise and took a cab to return to his home. To keep the rumour going his co-conspirators meanwhile had dressed up in phoney French uniforms with white cockades to wear and decorated their their own chaise with laurel boughs to parade around the town. This further evidence that the war was indeed over ignited the Stock Exchange and prices climbed.

Even though there is some doubt whether the telegraph actually worked that morning and de Bourg’s message ever got to London in that form, nevertheless de Bourg and his compatriots stirred enough excitement to see Government bond prices spike – exactly as the conspirators planned. They began selling hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of bonds they had bought the week before in a government stock called the Omnium, garnering profit ‘for their own lucre and gain’, as the indictment put it.

Except of course Napoleon wasn’t dead. At the battle of Brienne the previous month he had come near death when a corps of cossacks did indeed break through the lines and were heading for Napoleon’s tent, but they were seen off. Napoleon may have been losing the war, but he was very much alive. The British would not hear the last of Napoleon until the battle of Waterloo in 1815.

So this was a scam. Even then with communications as poor as they were, there were enough people arriving from France daily who would pretty soon absolutely refute De Bourg’s claims, so the broker worked quickly offloading the Omnium stocks.

Who was De Bourg? De Bourg, or to give him his real name, Augustus Charles Random de Berenger was a one-time colourist in an artist’s studio, volunteer soldier with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, a renowned shot with rifle and pistol and a debtor who had been confined to the ‘Rules of the King’s Bench’ for nearly a year and a half. The ‘Rules of the King’s Bench’ was an eruv or ghetto in Southwark around the King’s Bench prison itself, where prisoners could live their lives outside jail but still under sentence. Though incarcerated, de Berenger rented four rooms on the top floor of a house near the Bedlam lunatic asylum. He had enough leisure time to occasionally annoy his landlady by playing his violin or the trumpet. His servant (under the Rules of the King’s Bench servants weren’t forbidden) addressed him as Baron de Berenger, as he had the good fortune to marry a Prussian heiress. As he was the husband of a baroness, he could see no reason why not to call himself as baron.

It was indisputable that almost as soon as he got home de Berenger left again and got a cab to Lord Cochrane’s house, off Grosvenor Square. Thomas Cochrane the sailor and MP was a renaissance man. Alongside his naval and political careers he was an inventor. That morning he was in the factory district of Clerkenwell supervising the construction of a new, more powerful version of the ship’s light he had patented which he was to take with him on his next voyage.

De Berenger scribbled a note which was sent to Cochrane in the factory. Cochrane hurried home. Cochrane’s defence was that de Berenger was a stranger to him who introduced himself in the note and told him he was in prison for debt but allowed out on parole. He could never pay his debts so he was begging Cochrane for a place on his warship to America. Cochrane said he refused.

After the note from de Berenger Cochrane joined his ship, but as soon as he realised that word was out that this prime suspect in the fraud had been seen entering his house, he excused himself from his ship and went to the Stock Exchange to tell all he knew. All this did, sadly, was to give the government the excuse it needed to punish him for making waves.

In any event it is difficult to see how much more loaded against Cochrane the trial which began exactly 203 years ago tomorrow could have been. The lawyer for the Stock Exchange was a man whom Cochrane had already previously accused of fabricating evidence. That lawyer had been the lawyer for the man Cochrane called a coward. The lawyer in turn picked as prosecuting barrister a man that had clear conflict of interest, as Cochrane had gone to that same man to seek (as he thought) confidential professional advice from him as to what to do to clear his name. The judge’s summing up defied logic, but that may have been because the judge, Lord Ellenborough, was also a cabinet minister.

Cochrane’s bravado did not desert him, though his country did. Stripped of his rank and his seat in Parliament and had him thrown into the same King’s Bench jail. He was threatened with the ultimate ignominy for a gentleman — an hour in the public pillory, though that part of the sentence was not carried out. The electors of Westminster stubbornly stood by Cochrane and returned him again in the subsequent by-election. He broke out of prison and attended the House of Commons, there to be arrested and sent back to a more secure cell.

The Times ran the government line that his fall from grace had driven him insane, but that was plainly not so. He reluctantly paid a £1,000 fine (at least £60,000 today) to gain his freedom, but to show how wronged he felt, he wrote on the back of Bank of England £1000 note number 8202, dated June 26 1815 an endorsement. It reads “My health having suffered by long and close confinement and my oppressors being resolved to deprive me of property or life, I submit to robbery to protect myself from murder, in the hope that I shall live to bring the delinquents to justice.”

Discarded by England, the man the French had nicknamed loup de mer simply found himself another war. He distinguished himself as a naval tactician in Chile, then Brazil, then Greece. Eventually He was restored to his rightful place as one of the fathers of the 19th century Royal Navy, but not until 1847 would Queen Victoria re-instate his knighthood.

Also convicted in the Great Stock Exchange Swindle in his absence, Cochrane Johnstone was once more on the run – to France then back to Dominica. He returned to France but the scandal of further frauds on the French government were still hanging over him when he died in 1833.

De Berenger was chased to Sunderland, Newcastle and Edinburgh before being captured in Leith. He got a year for his deception, but you wonder whether he was threatened with much worse, for very soon after his sentencing he began to relate in great detail how the fraud had been planned and the central role that Thomas Cochrane played. He said that Cochrane was present in the meetings in the week before his trip to Dover, and that Cochrane saw the outline plan of De Berenger’s journey to Dover.

Fifteen years later, his appetite for risk never having deserted him, the baron, now richer through an inheritance, bought an 11 acre estate leading down to the River Thames from the King’s Road in Chelsea. He remodelled it as the famous Cremorne Gardens, which for four decades was London’s summertime haunt of party goers, pickpockets and whores.

Maybe another one of Thomas Cochrane’s naval enemies, the Earl St Vincent, was right in his Game of Thrones style assessment. Though when he said it he was alluding to Thomas’ uncles, he said this: “The Cochranes are not to be trusted out of sight, they are all mad, romantic, money-getting and not truth-telling—and there is not a single exception in any part of the family.”

Writing just before his death in 1860, Cochrane, then aged 85, explained it all away: “It was one set of stock jobbers and their confederates trying – by means of false intelligence – to raise the price of ‘time bargains’ at the expense of another set of stock jobbers, the losers being naturally indignant at the successful hoax. The ‘conspiracy’ – such as it was – was nevertheless one, which, as competent persons inform me, has been the practice of all countries ever since stock jobbing began, and is in the present day constantly practised, but I never heard mention of the energy of the Stock Exchange even to detect the practice.”

He was right. Time after time throughout that century and the next up to the present day, financial regulators seem content to do little or nothing to stop such market rigging.

The Hornblower series with the actor who was in Fantastic Four was excellent–really brought the books to life. He captured the idealism of Hornblower quite well.