Napoleon called the British a nation of shopkeepers. As the first Christmas of the 1914-18 war neared, those shopkeepers of Britain were concerned the country might be distracted from being a nation of customers. To remedy it for that year and throughout the war, much marketing effort was put into keeping the home tills ringing.

You could not beat hinting that what was right for the Royal Family is right for the masses, so in December 1914 a Derby stationer took those to task any who might be downsizing their Christmas in wartime. “Follow the Queen’s Lead” its advertisement bellowed. “Queen Alexandra has ordered her Christmas cards and presents — AS USUAL”. The queen in question was Danish-born Alexandra, the dowager mother of the monarch. She had always hated the Prussian side of Queen Victoria’s Saxe Coburg Gotha family, so you can bet that nephew Kaiser Wilhelm was off the Christmas list.

Khaki handkerchiefs, khaki gloves and khaki scarves abounded as Christmas gift ideas. One gift set covered all the bases for an emotional letter home from Flanders, with a writing pad, pencil and khaki hankie too. This brazen practicality was in keeping with other home front civilian present suggestions for the upper classes to dole out to the below stairs people. Stuck for what to give your servants questioned advertisements? How about a “new apron, cap or overall in reliable materials”?

A dry cleaner drummed up business by appealing to patriotic fervour, telling his readers not to buy new but to send their clothes to him. “Remember” he counselled, “Be patriotic and wear your old suit or costume for another year. Don’t buy new clothes… remember, if you do, you are taking the yarns that ought to have gone to make some soldier’s suit and he must wait — have you thought what the delay may mean? Think!” Any soldier doing the thinking would have been grateful indeed for the reprieve, deprived as he was for a few weeks of the chance of getting killed in France, while he waited for a uniform.

As air raids demanded blackouts, many shops across the country offered the gift for civilians that went on giving, as the radium content in both these articles was probably toxic. It was an anti Zepp Glow, a luminous glowing collar to wear so that people avoided bumping into one another on the darkened streets.

In a marketing ploy that is still familiar today, Rowntrees generously advertised a free large tin box for the troops, filled with chocolate, postcards and a pencil. All you had to do to get this free gift was collect the vouchers from thee pounds of cocoa. That’s a lot of cocoa.

Even patent medicine makers got in on the act. Zam-Buk was an unprepossessingly named antiseptic cream for family use, though its 1915 ad threw in for good measure that “its timely aid is also keeping many of our gallant soldiers fit for the firing line by saving the from reporting ‘sick’ with simple wounds or bruises.”

A more gruesomely practical gift was an identity tag. In the early years of the war soldiers were given one tag only. Of course the army had not thought it through. It issued an order that the tag should be taken from the corpse when a soldier was killed to record who had died. This left the body unknown and unidentifiable. Even after the High Command cottoned on to the logical problem and issued two discs, these were of fragile compressed asbestos rather than the more expensive tin. But for one guinea, a well heeled loved one could get a gold, hand engraved version with name, rank, religion and regimental crest from a London jeweller, Sims & Mayer in the Strand. For the less well off, they would do the same in silver for eight shillings or for four shillings in base metal. Dressing it up as “a souvenir that would last for years” belied its real purpose.

Newspapers saw the war as a circulation building experience. Subscription drives for digested weekly editions were often touted as ‘gifts for our brave boys’ at the front.

The bereaved, or those just fearful for their loved one’s survival, could send the Liverpool Echo five shillings and a photo of their soldier son or husband. They would get back a “faithful enlargement, beautifully tinted in subdued colours” as part of the newspaper’s Khaki Tints service during 1916. One testimonial read “You can almost imagine him speaking”, though you wonder whether his parents would ever hear his voice again.

As word filtered back about real conditions in the trenches, ads began to appear for items such as the Kergold Anti-Vermin Belt against lice and fleas. “A boon to soldiers; once worn, troubled no more” started to appear among the advertisements.

The horrific wounds of the war were becoming apparent to the general public as increasing numbers were seen on the streets. For Christmas 1916 Hill’s Rubber Company of Reading were listing “Gifts to comfort, cheer and amuse Our Brave Boys, their friends and kiddies”. Aside from a selection that included pillows, hot water bottles and waterproof coats for the men and balloons and dolls for the kiddies is listed “tough rubber pads for crutches”.

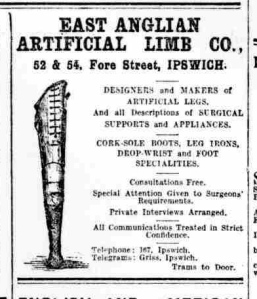

Once hidden among the rupture trusses, artificial limbs began to get more prominent exposure. Doubtless the fit, comfort, and usability of those bespoke limbs from the private sector outdid those that the government offered to wounded men, but like everything else in life, quality came at a price and that was almost certainly not affordable to most returning private soldiers.

Gift giving had a darker side. 400 cigarettes would make a nice present for a serving military man, or so thought Elsie May Cherrington, a “foolish lady clerk” in a Nottingham cigarette shop in January 1917. The problem was she stole the cigarettes from her employer. The soldier in question convinced her he was in fact a lieutenant in the Royal Flying Corps, which he wasn’t, though when it came to Elsie’s trial he had definitively flown. The merciful magistrate gave distraught Elsie two years’ probation. The good news was she got married that summer. Whether it was to the un-named soldier or not isn’t known.

Even at the end of the traumatic four years, the hucksters were undefeated. At the armistice they branded December 25th 1918 as the “Victory Christmas”  and tried to embarrass the populace into spending like before the war. And while some were desperately trying to sell off the bales of by-now redundant khaki nose wipes, the crowds were encouraged to shop early and “celebrate it in the good old way by giving useful and ornamental presents.” Survivors and the bereft were instructed to “Make your gifts worthy of a Victory Christmas”. With unaccountable pride the retail trade, which had been hiding behind its counter for the past four years was bracing itself to dip its hand into the war weary’s wallets. “We are ready for it… Are you?”

and tried to embarrass the populace into spending like before the war. And while some were desperately trying to sell off the bales of by-now redundant khaki nose wipes, the crowds were encouraged to shop early and “celebrate it in the good old way by giving useful and ornamental presents.” Survivors and the bereft were instructed to “Make your gifts worthy of a Victory Christmas”. With unaccountable pride the retail trade, which had been hiding behind its counter for the past four years was bracing itself to dip its hand into the war weary’s wallets. “We are ready for it… Are you?”

Reblogged this on First Night History.